Annexing the Arctic: 2024

How contemporary dating advice can help us understand Russia's relationship with the North Pole

Alexei Navalny’s shocking death in a remote Russian prison last month has renewed Western nations’ interest in the Russian Arctic. There have been numerous articles about Russia’s historic use of polar penal colonies, but only one expert seemed to connect this past to Putin’s present penchant for cruelty. In an interview with France24, Dr. Emilia Koustova commented about his use of “climate as a tool of repression.” The prison Navalny was held in, known as Polar Wolf, is located in a town 40 miles north of the Arctic Circle known for its snowy, alpine environment (note the mountains in the above photo’s background). Kharp sits right on the edge of the Pole in a region known as the tundra. Interestingly, the word is actually the exact same in Russian, for it originated in the Kildin Sámi (or Lappish) language by the indigenous Sámi people who called their home environment tūnter.

Per the Koppen Classification system, both the tundra (ET) and subpolar (Dfd) climates have very long, cold winters and short, cool summers; the main differences between the two is that subpolar regions receive constant precipitation whereas the tundra is drier and more frozen solid. By building the Polar Wolf camp on the border between these two climate regions, prisoners likely experienced the worst of both worlds in that they lived in a frozen environment that still had enough moisture in the air for frequent snow. But because of global warming, these environments are predicted to melt and thaw, which would only exacerbate the problem of climate change. So what’s to be done?

My very first post on In Circulation discussed the threat of climate change to the Arctic, both in terms of managing the environment and relying on Russian policies to lead the way (the country controls a majority of the land & sea territory, after all). Since planting a teeny flag on the geographic North Pole back in 2007, Russia has quickly accepted its increasing importance regarding the Arctic. In a book published just last year, scholar Elizabeth Buchanan argues that Russia has had the ability to take over the Arctic for a few decades now but has deliberately chosen not to. As she writes in Red Arctic: Russian Strategy Under Putin,

“Russia has gone to war with Georgia, wrapped a second battle in Chechnya, fought insurgents throughout the Northern Caucasus, and intervened militarily in Syria. And while Moscow may have absorbed Crimea and sustained military aggression towards Ukraine since 2014, it has yet to annex the North Pole. Why not?”

She raises an interesting point, one that’s often employed by straight women on Instagram giving dating advice: if he wanted to, he would! While this is usually spoken in reference to a man’s motivation to take someone on fancy dates or proclaim his true love, the idea itself is versatile. If one is confident enough in their abilities, or sees a course of action as beneficial, they will act on their desires. The main thesis of Buchanan’s book is that Russia needs global cooperation to achieve its national goals. However, I find it hard to believe that Putin has put his quest for supremacy entirely on the back burner for the good of mankind. Given the country’s historical use and abuse of their vast subpolar territory, it is more likely that Russia is exploiting collaborative frameworks with other nations, First Nations, and even scientists for their own gain.

A frigid history

Siberia and the Russian Arctic have long been associated with brutality and death. Great works of literature such as Aleksander Solzhenitsyn’s The Gulag Archipelago brought the realities of Russia’s prison system to life, particularly for English-speaking audiences as this book was banned by the Soviet Politburo. At its height, the Gulag, a collection of more than 400 forced labor camps, housed 1.7 million people, but historians disagree on the total number of people imprisoned by the Soviet government from the 1920s-1950s (estimates range from 14 to 25 million). Undisputed, however, is the total number of people who were worked to death — 2 million — while logging, mining, or constructing canals and railroads. Given the frigid environment, any who managed to escape were often found dead mere kilometers away from the camp. After serving their sentence, prisoners were oftentimes banished to remote parts of the USSR (Solzhenitsyn was sent to northern Kazakhstan, for example).

The Russian Arctic also accounts for a substantial share of Russia’s wealth, despite its harsh environments. The region is rich in wood, coal, oil, and gas, but its annual maximum temperature range is from -90°F/-68°C in the winter to 90°F/32°C in the summer! Much of the land is preserved in permafrost, which is defined as a layer of rock, sediment, ice and other organic material that remains frozen for at least two consecutive years. (Fun fact: permafrost can be found on both land and sea!) Because it completely covers nearly 65% of Russia’s territory, infrastructure is expensive and time-consuming to build.

What’s currently happening, climate-wise, to the Russian Arctic?

Although it’s an impediment to advanced human technology, permafrost has many climatological benefits. It is a repository for greenhouse gasses: water from the atmosphere falls onto the tundra, bringing trace amounts of gas with it, and when this water inevitably freezes, those gases become permanently contained in ice. This is why permafrost holds more land-based CO2 (roughly 1.4 trillion tons) than any other carbon sink in the world, including the atmosphere!

The most important greenhouse gas stored in the frozen soil is methane (CH4); although it makes up 0.00017% of the atmosphere, CH4 accounts for 30% of the warming! This is because the gas absorbs a different wavelength of heat than CO2 or water vapor, which together comprise a majority of greenhouse gasses. The more methane there is in the sky, the more effective our atmosphere will be at retaining heat. Normally, this phenomenon is great, for it keeps our earth at a livable temperature, but too much of a good thing is indeed bad for us.

Many recent studies demonstrate that soil temperature has increased by 1.4-1.8C in the past 80 years, resulting in a significant thawing of permafrost. This means that extra methane has been released into the air, which (as established above) absorbs more heat, resulting in higher temperatures and more permafrost melt, which releases more methane etc. etc. Scientists are already seeing an increase in average air temperatures in the western Russian Arctic, where Kharp is located. This type of process is known by climatologists as a positive feedback loop: one small change can and will become bigger as time goes on because of the kind of chain reaction it causes.

The consequences of permafrost melt are still being studied, but one group of scientists recently predicted this phenomenon could actually increase sea ice coverage in the coming decades. This would have a net cooling effect because sea ice reflects the sun’s rays before they can be absorbed by the earth, thereby diminishing the total amount of warming and beginning a negative feedback loop (the magnitude of change gets smaller as time goes on). Basically, thawing permafrost causes excess water to enter streams and rivers, which all flow into the Arctic Ocean. According to Kholoptsev et. al., this will increase the amount of water that enters the Arctic Ocean and enlarge the rivers’ point of entry into the sea. Usually, we call these areas “mouths” or “deltas” depending on the environment’s layout, but in polar climates they are known as polynyas, and it is in these protected bays of water that sea ice can safely form and thicken. So, warmer winters means more water will flow into these polynyas, causing more sea ice to form, meaning the environment in the Russian Arctic could be capable of self-regulation. Fancy that!

Lead the way?

Despite the complex potential of the Arctic, the Russian government has not taken as active a role in protecting it as one might think. According to an article in Climate Change magazine, Russia’s Arctic policies pay lip service to the threats posed by climate change without actually “contributing to resilient and sustainable growth in the Russian North.” After signing onto 2015’s Paris Agreement, Putin’s government wrote a series of documents addressing climate adaptation but buried the responsibility for creating actionable policies deep within their state bureaucracy. Moreover, the accelerated warming of the tundra has triggered anxiety about Russia’s economy, which is heavily dependent on oil reserves both within the Arctic Ocean and across Siberia. In order for drilling to occur, the environment needs to be stable (i.e. the permafrost needs to either be completely melted or completely frozen, the sea ice needs to be all over or extremely limited). Some companies have taken to building their rigs on top of piles so that cold air may circulate beneath the buildings and keep the ground frozen — this also has the benefit of keeping the expensive technology dry as permafrost melts. Adaptations like these neither help nor harm the environment, allowing humans (and corporations) to continue on a business-as-usual path.

Indeed, public policy researchers have observed that Russia’s main strategy for combating climate change is adaptation, not mitigation, suggesting that they don’t share the West’s view of climate change as an existential threat to humanity. Ilya Stepanov, a climate economist at the International Monetary Fund, wrote in the book Climate Security in the Anthropocene that climate change is viewed as an opportunity for national growth and enrichment, citing “the corresponding political discourse on potential benefits of growing transport and resource accessibility” in the Arctic. Because Russia comprises 53% of the Arctic Ocean coastline, its participation in international organizations such as the Arctic Council (AC) is effectively mandatory. It was the first chair of the AC from 2004-2006, yet despite its initial promise to facilitate “sustainable management of natural resources and wider use of renewable sources of energy,” it instead organized a symposium about exploring the extent of oil and gas deposits present in the region. Its second tenure as AC chair ended in 2023; one of their main accomplishments was encouraging the development of “environmental projects” in the Northern Sea Route, which is the area of the Arctic Ocean that will become increasingly navigable as sea ice melts. The continuation of global warming seems to be in Russia’s best interest.

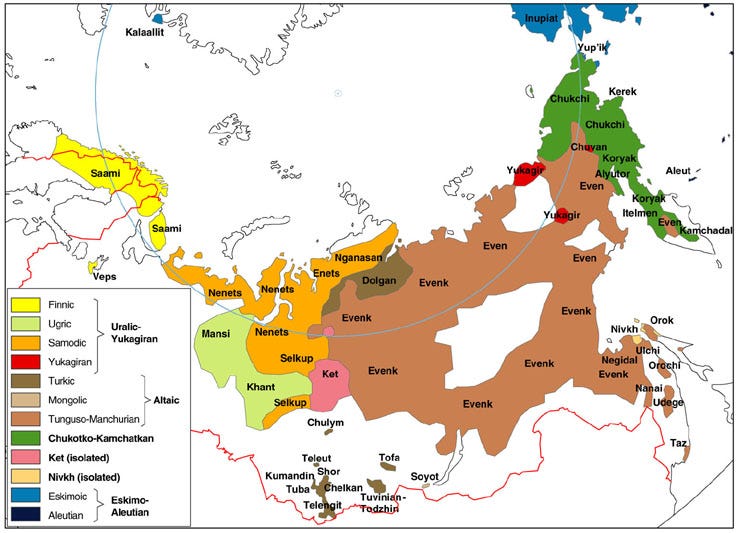

While the government concerns itself with acquiring the support of other nations to further its economic goals, it is the indigenous peoples in the Arctic that are charged with combating climate change. The Arctic Council was originally established to encourage countries to cooperate with First Nations towards a communal goal of environmental stewardship and has been a beacon of equality in the diplomacy world by tribal leaders and heads of state near-equal power. However, since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022, Western nations voted to pause Arctic Council meetings against the wishes of indigenous community leaders. This is just the latest in a long line of injustices faced by the 40 recognized indigenous tribes, who are often the first to experience the effects of climate change. As you can see from the map below, the tribes’ homeland comprises nearly all Russia’s Arctic Circle territory and most of Siberia — the exact regions where the Russian state and international companies such as BP and Total SA are drilling for oil and gas. Since there is no cooperative framework between indigenous groups and the private sector, these communities could see their land and resources exploited.

To combat this power imbalance, the Russian government in 1990 created RAIPON (Russian Association of Indigenous Peoples of the North), a political organization that supposedly represents tribal interests within national & international governing bodies. However, as I reported last year, Russian support for Arctic peoples seems to be conditional: shortly after the 2022 invasion of Ukraine, RAIPON issued a statement supporting the ‘special military operation’, which evidenced claims that the group has been co-opted by Putin in recent years. Indeed, his Ministry of Justice forced RAIPON to close from 2012-2013 so that a new pro-Putin indigenous leader could be installed — Grigory Ledkov assumed office almost a year to the day before Russia invaded Crimea. Currently Ledkov is under personal sanction by the EU, US and at least 6 other countries because of his unwavering support for Russia’s war in Ukraine, which effectively prevents any dialogue between non-Russian governments and Arctic indigenous groups.

Conclusions

Russia is the largest country on earth with territory bordering three of the five major oceans (Atlantic, Arctic, Pacific). In addition to their vast territory, they also are a giant in international policy with a permanent seat on the UN Security Council and representation within the European Union. However, Russia sees this international desire for cooperation about the Arctic as confirmation of their superiority. In recent years, Western supranational organizations (such as the Group of 8, now known as the Group of 7) have removed Russian diplomats from their orbits due to the country’s propensity to invade its neighbors. Some policy researchers, such as Moe et. al., believe that the isolation of Russia “will make it difficult to influence Russian climate policies” since the nation’s climate policies are dependent on “international cooperation and integration of Russia in the world economy.” By excluding the nation from the world stage, Western countries may have de-incentivized any renewable energy innovations or low-carbon policies.

On the flip side, it is the responsibility of Russia to act as good-faith partners in the fight against climate change. As observed by the Arctic Institute, many European countries are looking to the Arctic “as supplier of resources necessary for the ‘green’ transition and energy independence from Russia.” Despite this, Putin’s government recently announced that Russia would allocate funding to increase oil and gas production in the Arctic twofold in the coming decades (those newly accessible seabeds aren’t going to drill themselves, after all!). Even though it has been well-established by Russian scientists that the methane from melted permafrost and relative dearth of sea ice is wreaking havoc on the planet, Russia has seen Western nations’ retreat from non-renewable energy sources as their chance for more power.

So, instead of adopting Elizabeth Buchanan’s assertion of “if he wanted to he would,” which implies that Putin is a passive partner in the Arctic, we should instead realize that Putin does want to position himself and his country on top of the world order. He has set a precedent for caring about collaboration only when he is assured a majority stake, as exemplified by Russia’s continued participation in the Arctic Council (at least until 2022). The Arctic is the only place on Earth where Russia’s authority is difficult to question: Putin can not only reign supreme, but also get other countries on board with his agenda. The fact that he has not taken measures to start an all-out war in the Arctic does not mean, as Buchanan wrote, that he values cooperation — it means he thinks he’s already won.

Main Sources

Arild Moe, Erdem Lamazhapov & Oleg Anisimov. “Russia’s expanding adaptation agenda and its limitations.” Climate Policy, 23:2, 2023, pp. 184-198. DOI: 10.1080/14693062.2022.2107981

Buchanan, Elizabeth. Red Arctic: Russian Strategy Under Putin. Brookings Institution Press, 2023.

Hodgson, Tommy. “Indigenous Climate Action in Russia.” Shado Magazine, 19 Aug. 2021, shado-mag.com/do/how-the-indigenous-people-of-russia-are-reclaiming-their-land-and-the-climate-narrative/. Accessed 19 Mar. 2024.

Kholoptsev, A.V., Shubkin, R.G., Baturo, A.N., Babenyshev, S.V. (2023). “Climatic Changes in the Arctic Zone of Russia and Climate Warming in Siberia.” In: Processes in GeoMedia—Volume VI. Springer, pp. 217-228. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-16575-7_20

Papachristou, Lucy. “What We Know about Alexei Navalny’s Death in Arctic Prison.” Reuters, 19 Feb. 2024, www.reuters.com/world/europe/alexei-navalnys-death-what-do-we-know-2024-02-18/. Accessed 14 Mar. 2024.

Scollon, Michael. “At Risk: Russia’s Indigenous Peoples Sound Alarm on Loss of Arctic, Traditional Way of Life.” RadioFreeEurope/RadioLiberty, RFE/RL, 28 Nov. 2020, www.rferl.org/a/russia-arctic-indigenous-peoples-losing-traditional-way-life-climate-change/30973726.html. Accessed 14 Mar. 2024.

Stepanov, Ilya. “Climate Change in Security Perceptions and Practices in Russia.” In: Hardt, J.N., Harrington, C., von Lucke, F., Estève, A., Simpson, N.P. (eds) Climate Security in the Anthropocene, Springer, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-26014-8_10