Annexing the Arctic 2025

"You never really understand (an ocean) until you consider things from his point of view." -Harper Lee, mostly

From a terrestrial perspective, the United States’ plan to annex Greenland makes little sense. At 836,300 square miles, four-fifths of the island is covered by an ice sheet. To get from one town to another, one must travel via small plane, boat or dog sled as there are very few roads. Although its closest neighbor, Canada, is just 16 miles away, Greenland has stronger cultural ties to Denmark and uses the Euro for all domestic and international transactions. As a result, many political commentators have puzzled over President Donald Trump’s repeated attempts to gain control of the territory. Some believe it’s a political trap to ensnare Democrats while others think such blatant ambitions would encourage America’s adversaries to expand their territories. While his original promise to do so in his first term ultimately came to naught, Trump’s demonstrated record of making big (and illegal) policy moves in his second term has made the Danish and Greenlandic governments uneasy.

Previously on In Circulation’s Annexing the Arctic series I wrote about Russia’s territorial claims in the Arctic and Putin’s corruption of indigenous organizations. My newsletter also focused on the US military’s climate change plan under President Biden, which discussed potential repercussions of climate-change-induced ice melt and sea level rise. This year, however, I am compelled to expand this series to include territorial ambitions by the second Trump administration. Environmentalists and political commentators tend to interpret this claim as Trump wanting to expand America’s oil fields and ‘drill baby drill.’ By focusing overwhelmingly on fossil fuels, as the climate change narrative often does, one misses out on the bigger picture: this ‘land grab’ is actually not about land at all. This week on In Circulation we’ll learn how valuable Greenland’s waters are, both environmentally and politically, and the increasing militarization of this vulnerable environment.

“I see (lands) of green…”

One of the first Fun Facts on Greenland’s tourism website is that an exiled Icelandic murderer intentionally misnamed the island ‘Greenland’ to entice people to move there (whether he intended to get new neighbors or new victims was never determined). These original Viking settlements disappeared after a few hundred years; while today only 12% of the population are ethnically European, the original settlers left a great impact on Greenland’s culture and farming practices. In the past the largest export was ivory from walrus tusks, but nowadays the country’s wealth is stored deep beneath the surface. Colder environments tend to be nutrient- and resource-rich as proved by the US Geologic Survey. In a 2007 survey of Greenland, USGS found that it has between 8,000-9,000 million barrels of oil and natural gas each and 86,179 units of gas, enough to power the US for four to five years! The area is also rich in zinc, gold, nickel and other rare earth metals necessary to power electric cars, computer chips and the like. Most of these valuable resources are buried under layers of permafrost and land- and sea-based ice, or are found on the ocean floor. Since they will become increasingly available as our planet warms, the value of Greenland’s territory will increase exponentially by the end of this century.

These minerals were likely deposited during the Pliocene and Pleistocene Epochs when Greenland boasted a warm, verdant environment. By looking at plant and animal DNA found within ice and sediment cores, Nordic scientists revealed in 2022 that around 2 million years ago Greenland was home to mastodons, horseshoe crabs and a wide variety of shrubs and fir trees! Nowadays the only pockets of livable land are on Greenland’s southwestern coast, where there is a slight influx of warm water. Although most maps of ocean circulation show the Gulf Stream passing well south of Greenland, a small part of the current actually floats up into the Labrador Sea. When this warm water comes into contact with the extremely cold polar waters, it cools down by releasing its heat into the atmosphere. This evaporation causes the air along Greenland’s nearby coast to hold more moisture, allowing for a more moderate and livable climate than other parts of the island.

Ice Ice Melting

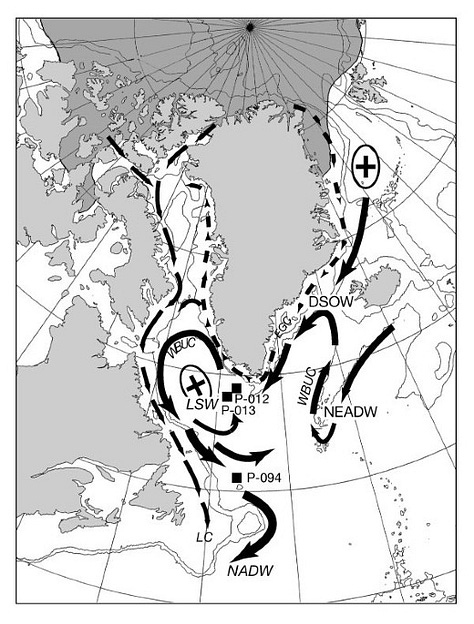

Because of this evaporation, the surface water becomes saltier and denser and sinks down to the bottom of the water column. This part of the global ocean circulation is called Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) and it is vital to the regulation of Earth’s entire climate. When cold surface water sinks, it makes room for more water from the tropics to flow northward, ensuring the cycle replenishes itself. If we remember from previous In Circulations, a parcel of water will travel through each of the five major oceans over a period of 1,000 years, and because all oceans are connected any change in the motion of water in one part of the world will have a ripple effect (pun intended).

In the past, increases in solar radiation or the speed of Earth’s orbit greatly altered ocean circulation, but today scientists are worried about one thing: meltwater. Because the globe is over 1°C warmer than it’s supposed to be, the land-based ice in Greenland has been melting steadily for several decades. The island’s huge freshwater glacier is losing 277 Gigatons of mass each year — to put that in perspective, the mass of all land animals in the world is merely one Gigaton…! As you can see in NASA’s video below, the largest pockets of ice mass loss are close to the habitable coasts of Greenland, which are in turn closest to the warm Gulf Stream waters. While scientists are still figuring out why some portions of the Greenland Ice Sheet are more vulnerable than others, this increased melting has led to dangerous floods.

Besides the obvious effect on sea level rise and threat to human populations, this influx of meltwater will minimize the temperature differential between the Gulf Stream waters and the cold Arctic environment. But will this cause the AMOC to disappear, or will the downwelling of warm tropical waters merely happen further south in the Atlantic Ocean? This question is currently the main driver of physical oceanographic research. After a 2018 study showed the AMOC has been weakening since the mid-20th century, researchers Devilliers et. al. created a model that showed the melting of the Greenland Ice sheet would only be partially to blame for the AMOC’s slowdown. Still, an earlier study by Hu et. al. demonstrated lots of Greenlandic meltwater would cause a stoppage of the AMOC, which they posit would slow down any warming in northern latitudes. This would effectively strengthen the temperature differential between the tropics and the poles, meaning our climate could self-regulate.

Empire State Of Science

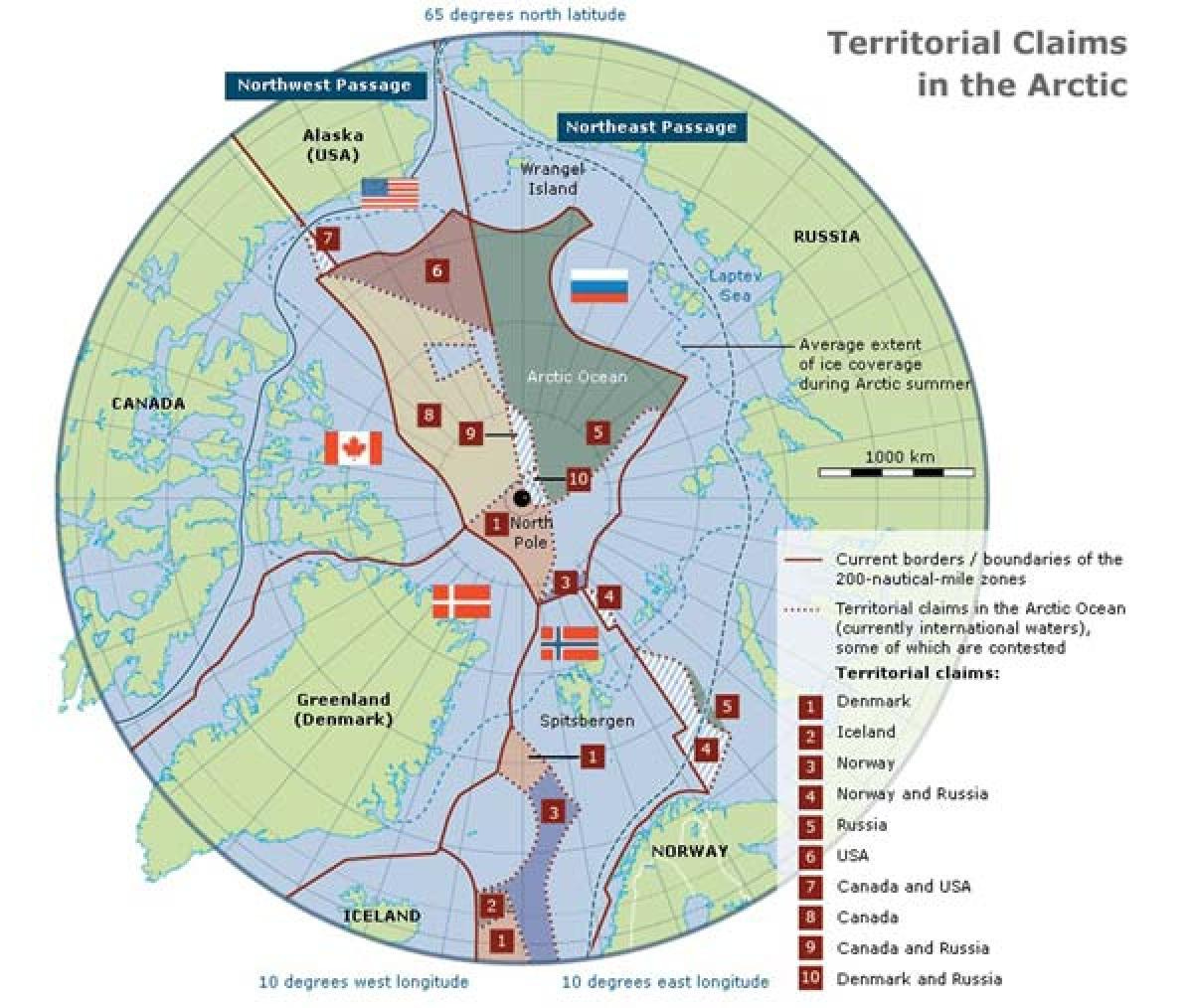

Since the studies surrounding this valuable environment are varied and inconclusive, it’s no wonder nations are using Science™ to enhance their standing on the international stage. Only five countries (Denmark, Norway, Canada, USA and Russia) have territory bordering the Arctic Ocean, but three others’ Exclusive Economic Zones extend into Arctic waters (Sweden, Iceland and Finland). Of these eight Arctic States, the US is the primary funder of research projects: in 2023 it spent over half a billion dollars on Arctic research with the majority of the funding coming from the National Science Foundation and the Department of Defense. Indeed, the Arctic has become Ground Zero for the militarization of science partly because of overlapping territorial claims and increasing aggression between the US and Russia. After the latter planted a flag on the geologic North Pole back in 2007, Denmark drew up the Ilulissat Treaty which clarified that no one country owns the Arctic Ocean. In doing so, the Danes gave up their own claim to the Pole, which sits closest to their Exclusive Economic Zone (while Greenland has been self-ruling since 2009, Denmark is responsible for the island’s foreign policy and national security).

Because of the highly publicized and anticipated environmental changes to the region, other global powers are trying to get their feet in the door. China has declared themselves a “Near Arctic State” and as of 2022 has invested almost $100 billion to establish ties with the Arctic. Whether of the scientific or militaristic nature is yet to be seen because there are currently no openly-accessible resources showing the location of research vessels around the globe. This is not due to a lack of technology, however: an organization called SkyTruth operates Cerulean, the only open-source tracking system for oil spills around the globe. At a recent webinar by the Nature Tech Collective, I asked their Chief Technology Officer Jason Schatz whether their satellites and software could be adapted to keep track of research vessels. He and Global Fishing Watch’s Paul Woods assured me that this was possible, having collaborated with the US Department of Defense to monitor deep sea mining explorations (the practice is frowned upon but not technically banned). However, any data about where these ships are conducting research is not publicized by their governments to avoid any security threats. Thus in environments made vulnerable by climate change, there has been a logical yet counterproductive conflation of military with scientific prowess.

Conclusion: Sympathy For The Arctic

Knowing the location of scientific ships would help researchers know with whom to share data and resources, yet a sense of mistrust and compulsive secrecy prevails even in the face of scientific integrity. This wasn’t always the case, however: foreign nations used to collaborate on polar science projects, and there was broad support for doing so. In 2017 the Arctic Council states signed the Arctic Science Agreement which guaranteed safe access to designated research areas in the Arctic Ocean. While any scientific cooperation has been put on hold since Russia invaded Ukraine in 2022, some environmental activists argue that recentering the environment with “science diplomacy” will pacify relations and benefit humans & oceans alike. Indeed, conservationists and proponents of Indigenous rights have long been advocating for policymakers to reframe their perspective on the ocean. Western culture has traditionally Otherized the sea, seeing it as an external entity that operates independently of humans. While this has led to the marginalization of historical and traditional knowledge as discussed in last week’s In Circulation, it has also prevented us from understanding our interconnectedness to the sea. By centering the ocean in all climate change adaptation programs, global citizens could protect and preserve the environment much more easily.

The Arctic Institute published an extraordinary article last month explaining the history and logic behind American designs on Greenland. As one of the few organizations that work to protect Indigenous rights and promote security in Arctic waters, it cannot afford to view Trump’s ambitions as a joke. The Institute argues that America’s renewed interest in the island is an opportunity for Greenlanders to assert themselves more prominently on the international stage. Put differently, by becoming the center of attention Greenlanders have gained legitimacy and can now save their culture and resources from (further) exploitation. This theory got me thinking: if Trump’s imperial desires can be seen as a good thing for “North America’s first and only truly Indigenous state,” is the outlook similarly positive when you consider the Arctic Ocean itself as a political agent?

When looking at the world from the Arctic’s point of view, there appears to be a large land border broken up by two significant gaps: the Bering Strait and the Greenland Sea. Although it’s dotted with islands and fjords and inlets, the Arctic’s coastline looks rather like a pair of parentheses: on one side is Alaska, Canada & Greenland, with Russia and Norway making up the other. Yet this parenthetical set is far from empty: if the sea had a seat at the table, it would dispel any expansionist notions from any of the Arctic States simply by existing. In other words, understanding the ocean’s right to exist (which many believe can be best achieved through a scientific quest for knowledge) would make we humans better stewards of our environment.

And anyways, if you were the Arctic Ocean wouldn’t it be easier to have quiet neighbors instead of confrontational busybodies? If only allied nations were in charge of your borders, they could more effectively limit shipping traffic, prevent oil spills, and monitor sea ice loss. They may even be inclined to establish Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) around Greenland to protect deepwater formation sites and limit drilling & deep-sea mining off the Eurasian coast. But if the only two people nearby were adversaries, like the US and Russia, the Arctic risks being taken advantage of as it faces the intensifying threats of climate change. When countries view oceans not as freely-existing bodies but as territory that is waiting to be conquered, then the Arctic and all others will become secretive, watery battlefields.

Sources

The Arctic Institute | Newsweek Russia claims Alaska and other nations | VisitGreenland.com | NOAA information on the AMOC | CNN what Greenlanders think of Trump’s proposal | World Energy Data article on the end of the AMOC | MIT Climate Portal slowing of the AMOC | Reddit territorial Arctic claims map

Caesar, L., Rahmstorf, S., Robinson, A. et al. (2018). “Observed fingerprint of a weakening Atlantic Ocean overturning circulation.” Nature vol. 556, pp.191–196. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-018-0006-5.

Devilliers, M., Swingedouw, D., Mignot, J. et al. (2021). “A realistic Greenland ice sheet and surrounding glaciers and ice caps melting in a coupled climate model”. Climate Dynamics vol. 57, pp. 2467–2489. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00382-021-05816-7.

Hu, Aixue, Meehl, Gerald A., Han, Weiqing, Yin, Jianjun (2011). “Effect of the potential melting of the Greenland Ice Sheet on the Meridional Overturning Circulation and global climate in the future.” Deep Sea Research Part II: Topical Studies in Oceanography, vol. 58, issues 17–18, pp. 1914-1926, ISSN 0967-0645. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsr2.2010.10.069.

Kjær, K.H., Winther Pedersen, M., De Sanctis, B. et al. (2022). “A 2-million-year-old ecosystem in Greenland uncovered by environmental DNA.” Nature vol. 612, pp. 283–291. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-05453-y.

Nghiem, S. V., D. K. Hall, T. L. Mote, M. Tedesco, M. R. Albert, K. Keegan, C. A. Shuman, N. E. DiGirolamo, and G. Neumann (2012). “The extreme melt across the Greenland ice sheet in 2012.” Geophysical Research Letters, vol. 39, L20502, doi:10.1029/2012GL053611.

Phelan, J. (2007). “Seascapes: Tides of thought and being in Western perceptions of the sea.” Goldsmiths Anthropology Research Papers (GARP 14). Goldsmiths College, University of London.

Seidenkrantz, MS., Kuijpers, A., Aagaard-Sørensen, S. et al. (2021). “Evidence for influx of Atlantic water masses to the Labrador Sea during the Last Glacial Maximum.” Scientific Reports vol. 11, no. 6788. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-86224-z.