Birds: the gateway drug of the climate crisis

How to harness the power of our avian friends & teach people about climate change

For the past six years, the Audubon Society has organized a bi-yearly event called Climate Watch, where backyard birders record which species they see over the course of four weeks. Not only is it popular with thousands of people participating each year, it also provides researchers with tons of raw data, which they then use to redraw habitat maps of birds to see how their migration patterns change. Click “play” on the video below for Audubon’s pitch to birders:

Climate Watch is an excellent example of a citizen science project that is simple, accessible, and successful. People are encouraged to spend a little time in nature and learn to identify birds with help from Audubon’s Bird Guide app. In choosing to help the ornithologists with their research, members of the public discover the value of the scientific method. When people are taught to notice the natural world, they feel closer to it, thus developing a sense of ecological (and perhaps aesthetic) proximity.

Oxford University’s Dr. Jamie Lorimer studied the idea of nonhuman charisma, or the idea that something outside of the human race can appeal to us. There are three different kinds of charisma (corporeal, aesthetic, and ecological) that increase our emotional proximity to a particular species or environment. I discussed these concepts in depth in previous newsletter: read it here.

Harnessing the tools of science and sending them out to be used by non-scientists is helpful for two reasons. One, researchers have access to much more data than they could ever collect on their own at a fraction of the cost. And two, the idea of ‘science’ becomes practical, familiar, and meaningful to everyday people. The Climate Watch project is bridging a crucial knowledge gap and causing people to feel inextricably connected to the changes happening in their world. But above all, becoming involved in something trendy & important is fun — I know I am enjoying participating this year!

The Audubon Society, which has been around since 1896, was founded by two women who were outraged over the slaughter of millions of egrets and other waders for the millinery (hat) trade. Coast-dwelling birds and other species of waterfowl have always been at the forefront of Audubon’s advocacy — their logo even depicts a snowy egret in flight. As covered in previous posts, most people feel disconnected from the oceans because they live inland & do not encounter it in their everyday lives — or in other words, the oceans lack ecological charisma. However, the Audubon Society has successfully carried the plight of the seas to the people on the wings of waterbirds. Is there a lesson for ocean literacy advocates in Audubon’s achievements? And how could climate scientists repurpose Audubon’s strategies to get the public to care about the ocean?

Go Set A Watch(man)

In order to understand why the initiative came to be, let’s explore its origins. Climate Watch is not the Audubon’s first community science project: the Great Backyard Bird Count has taken place every February for the past 25 years. They also organize the Christmas Bird Count (CBC), which began 1900 when ornithologist & field guide writer Frank Chapman proposed it as an alternative to hunting. This annual event is now the longest-running bird survey in the world. Data collected by amateur birders & budding ornithologists has proven extremely helpful to scientists. Indeed, earlier this year a study analyzed the distribution of nine birds species along the US East Coast using data from the CBC. These researchers found that spatial variations in birds’ habitats are being caused by climate change. As resources become scarcer, “effective land management will be critical for improving species’ resilience to climate change,” they concluded. Moreover, shifts in land usage, both anthropogenic (e.g. urbanization) and environmental (e.g. natural disasters), caused waterbirds to experience twice the magnitude of changes (migration patterns, habitat area, etc.) than other species that have larger, less specified habitats. The scientists’ findings coincide with the IPCC’s recent conclusions on human mitigation & adaptation to climate change, illustrating the broad reach of global warming.

This landmark ornithological study would not have been possible without data from Audubon’s public science initiatives. In recent decades as climate change has creeped towards the forefront of our minds, Audubon realized the need for a more comprehensive bird survey. In 2016 they started Climate Watch, which tracks the migration & average population density of different species of birds in order to compare the birds’ current seasonal range with that of previous decades. The survey takes place every winter & summer (January 15-February 15 & May 15-June 15) in order to accurately measure the effect of warming on avian populations. According to Audubon’s predictions, certain easy-to-identify species (e.g. the Eastern Bluebird) are expected to shift their seasonal habitat; volunteers observe spaces within both the birds’ current habitats and their predicted new ones. This way, when Audubon will know exactly when these changes area happening. Volunteers can claim a “square” via Audubon’s map; once their observations are completed, the raw data is submitted to local & regional coordinators, who then send it onto Audubon.

Survival By Degrees

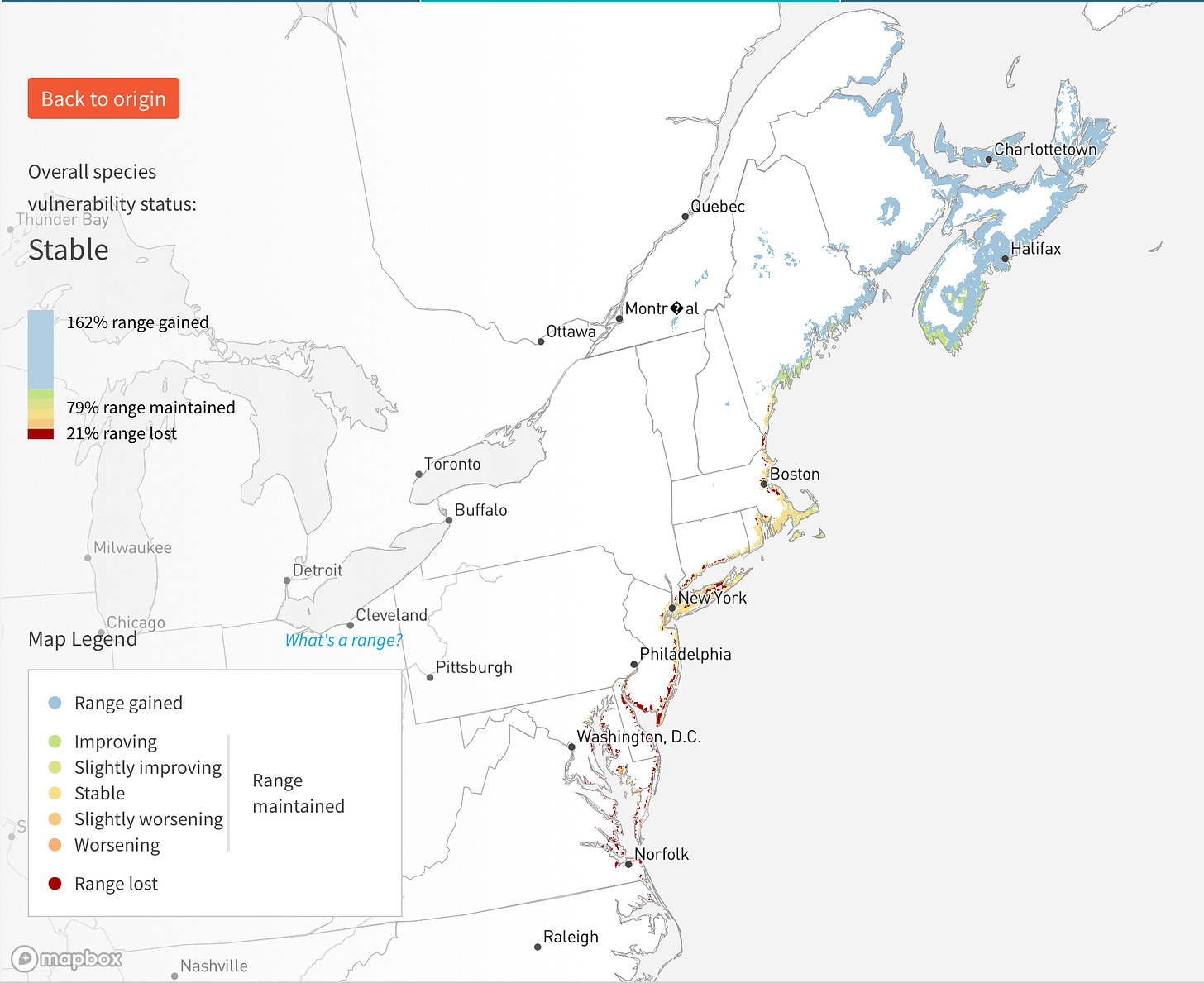

Scientists at the Audubon Society published a study in 2019 detailing how 2/3rds of America’s birds are at risk of extinction from climate change. But there is some good news: if warming is kept to 1.5°C maximum, 76% of at-risk species can be saved! They used data from scientific studies as well as observation records from birdwatchers across North America in order to create a list of vulnerable bird populations for each zip code. They also provide a map showing which and how many factors will affect birds as temperatures move from 1.1°C above average to 1.5, 2, and ultimately 3°C. In the Washington DC area, the largest threats to birds over the next two decades are urbanization (habitat destruction), heat waves (both extreme temps and unseasonable warmth), and sea level rise. Some birds’ habitats will shift northward; others will see their migration patterns shortened or halted altogether as the climate warms. The Audubon Society notes that species that take up residence in new environments (i.e. farther north, more mountainous, less frequent storms, further inland away from rising waters) will not be ‘safe’ from extinction. These new areas may fit within the bird’s temperature range, but the type of environment (i.e. urban/suburban as opposed to rural) could pose new and unique threats to the species. Furthermore, coastal bird species will experience catastrophic habitat loss as nesting sites become inundated with water as sea levels rise. Some, like the Saltmarsh Sparrow, nest in low-lying marshes along the Atlantic coast. As more marshland is flooded and destroyed by SLR, Saltmarsh Sparrows won’t anywhere to move into.

In keeping with our interactive map theme, Audubon created a visual representation of their findings: you can access it here.

The gateway drug to ocean literacy?

Birds are affected by climate change differently. While some can live in a wide range of environments, others need very specific foods and can only live in specific places. Everyday woodland species like the Wood Thrush are likely to disappear from the average person’s view in the next decade or so. If something so wide-ranging as climate change affect the birds in your neighborhood, imagine what will happen to those who depend on the ocean! This crisis of warming temperatures is causing an infinitely complex ripple effect in environments both land and sea. Whether we notice or understand them, the physical and chemical changes happening to our ocean pose as great great a threat as heatwaves and severe storms. Each and every habitat on this earth is connected — you cannot have storms without an ocean or acidification without greenhouse gas emissions. Once we convince humans to care, the path to cooperation and conservation will be straightforward.

The Climate Watch survey gives people an opportunity to help combat the climate crisis. They are given an outlet for their frustrations and encouraged to take action to on behalf of an organization that is fighting for something they care about. We see and hear birds every day: if people can cherish the sparrow chirping outside their house, they can certainly care about the fate of the Piping Plovers. In short, Audubon uses land-based woodlands species as a ‘gateway drug’ to waterfowl. Only once we arrive, emotionally, at the seaside can we collectively engage with the unique problems of our coasts. Birds are tangible & attractive harbingers of climate change, and our curiosity will no doubt get the better of us when we are taught to notice, study, and appreciate them.

What would a similar, ocean-focused project look like?

Climate Watch has inspired many non-scientists to draw attention, literally, to the plight of our birds. Audubon is sponsoring a mural contest where artists depict species of birds that are being threatened by climate change. Most of these are painted in the Harlem and Washington Heights neighborhoods of NYC, where John James Audubon, the society’s namesake, lived during the mid-19th century. Of the 100 birds painted, roughly a third of them live in coastal wetlands or ocean waters. Audubon already has a blog to describe each mural and explain why each species could become extinct as our planet warms. Yet there is no link between these paintings and the scientific knowledge they are allegedly illustrating. To fix this, the Audubon Society should create QR codes to be drawn on the side of the murals. These would link to an article on Audubon’s blog explaining the specific threats to the relevant bird species (sea level rise, excessive precipitation & storms, etc.). That way, members of the public could enhance their awareness with some education instead of just looking at art and walking away.

Another idea would be to create a community science program similar to Audubon’s Climate Watch. Instead of counting birds, people could measure sea level rise using their footsteps as measuring tools. Hear me out:

During the summer, when there are the highest number of people at the beach, people could measure the extent of the tides as a proxy for SLR and storms. Local group leaders could partner with lifeguards to put markers next to their chairs denoting where 50ft from the beach’s beginning is; beaches without lifeguards would partner with the state, local, or county park authority.

Each day at peak low tide, SLR volunteers could walk from where the waterline is to the preset markers. Volunteers measure the distance in paces and then record the length in in/cm of their foot in order to determine how far the water is from the beach. They would do this once a day, at either high tide or low tide (ideally you would have enough people coming at different points of the day such that you could get each measurement). Generally speaking, sea levels are higher (aka water is further up the beach) when there is a storm coming; they are lower (aka water is farther down the beach) after a storm has passed.

They would either 1) record this data on paper and upload a picture to an app or 2) type the data directly into the app. There would be people, like me, reviewing the data to ensure that each number is in the correct format. The computer program behind the app would synthesize it all into a spreadsheet; at the end of each week the map on the app would be updated with the data collected.

At the end of the summer, we would be able to calculate the average location of water on the beach and compare that data with the measurement we collected at the summer’s start.

Over the course of the next 10 years, or at least until the end of the UN’s Decade for Ocean Science, people would map the extent of the tides at their closest shoreline. Since SLR is happening pretty fast, we will be able to notice a change in a matter of just two to three years!

Wow, all that came from thinking about the fate of some Piping Plovers and Saltmarsh Sparrows... Just think of what we, as a society, could accomplish with birds as our inspiration! If you have an idea for citizen science project, feel free to leave a comment.

Sources

About “Survival by Degrees” (Audubon Society, July 2020)

“Climate Change and Birds Near You” article (Audubon Society, 27 May 2020)

Climate Watch page (Audubon Society)

Sarah P. Saunders, Timothy D. Meehan, Nicole L. Michel, Brooke L. Bateman, William DeLuca, Jill L. Deppe, Joanna Grand, Geoffrey S. LeBaron, Lotem Taylor, Henrik Westerkam, Joanna X. Wu, Chad B. Wilsey, Unraveling a century of global change impacts on winter bird distributions in the eastern United States, Global Change Biology, 10.1111/gcb.16063, 28, 7, (2221-2235), (2022).

Survival by Degrees study (Audubon Society, July 2020)