Eco-anxiety, or Why we're choosing the worst adventure

Featuring the Interactive Climate Atlas (aka if the Climate Reanalyzer and our human tendency to catastrophize had a baby)

Lately everyone seems nostalgic for our pre-COVID times when gathering in person didn’t result in tons of positive cases (looking at you, Gridiron and White House Correspondent’s dinners!). This desire for blissful simplicity has been absorbed by an internet subculture that wistfully memes about our pre-adult life, when the best part of our year wasn’t getting basic necessities as Christmas gifts but skipping part of school to visit the Scholastic Book Fair.

After spending my allowance on mini encyclopedias & mythology books, I always sat on the floor and read the choose-your-own-adventure tales. These stories were usually about a treasure hunt or a mystery; whenever it came time for the characters to make a big decision (say, whether to follow the footprints or which clue to investigate first), the reader got to decide what happened next! (i.e. “to follow the footprints, turn to page 40; to ignore them, turn to the next page”) You’d then flip to the designated section of the book and resume reading until it was time for another choice. This encouraged creativity — and revealed whether one was an optimist or a pessimist. Oftentimes I’d check out the first sentence of each option before continuing on to see which one was the ‘best’ — although in hindsight, it was equally as easy to choose the ‘worst’ option.

In the choose-your-own-adventure book that is climate change, it appears as though humanity keeps considering both storylines and choosing the worst one. After all, it is easier to simply keep flipping the pages instead of actively searching out your preferred ending. When ignoring advice that would point us in the right direction, it is easy to go down a rabbit hole of doom, especially in today’s world where we have access to endless amounts of information. Not all of it is true (or helpful) of course, which is why one must cultivate a clear understanding of the science so that negativity doesn’t become so overwhelming.

The drawback of aesthetic charisma

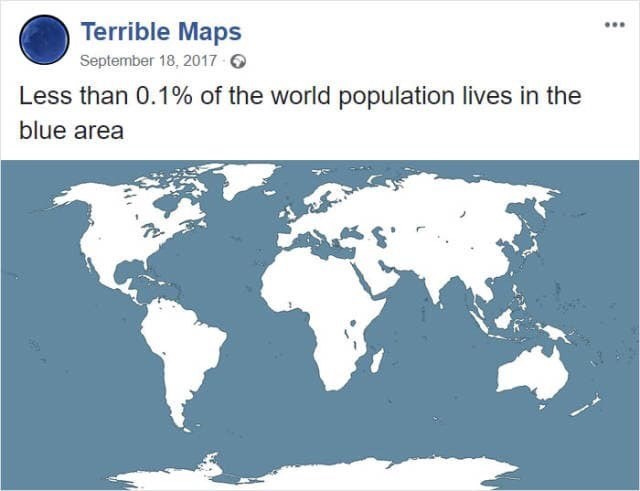

The main problem with our perception of oceans and climate change is that there is usually too large an emphasis on the effects instead of the facts. That is, journalists devote more time to discussing what will happen to the cute little seals, whales, and polar bears than to explanations of the ‘hard’ science. This is done to engage readers’ emotions as well as (or in place of) their brains, for mammals and other animals have aesthetic charisma, meaning we believe them to be attractive and therefore deserving of our attention. I am not arguing that seals are not important, but we should at least pay equal attention to any alterations in ocean chemistry or sea surface temperatures that would jeopardize their habitats.

Advocates & activists tend to catastrophize, portraying the worst possible outcome of an action or event as the most likely. This adversely affects both the well-informed and the skeptics alike, activating their “Myside” biases, which is the delusion when a person only sees information that supports their opinion. Climate- and ocean-illiterate folks are naturally suspicious of those with knowledge & power, and they will feel repulsed by disaster predictions, believing that the mainstream media creates too much drama. Data-deficient articles do little to convince deniers that their lives will be affected by our global problem; after all, would you be inclined to accept the claim that ‘we’re responsible for the extinction the polar bears’ if the writer barely explains the evidence? In short, when science is sidelined, humans react emotionally to any anecdote detailing our climate’s woes. Arguments that lose the guidance of logic become more and more heated, mirroring what is happen to our planet. To understand why climate change is such an emotional issue — and to meaningfully engage with skeptics — we ourselves must believe the facts to be compelling enough to drive our discussions.

Ocean illiteracy fuels the fires of climate anxiety

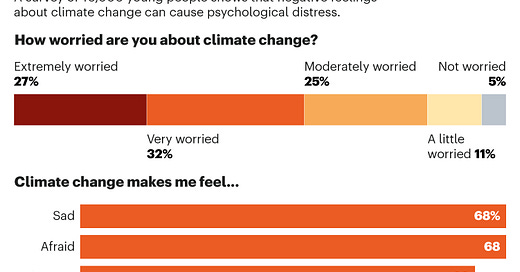

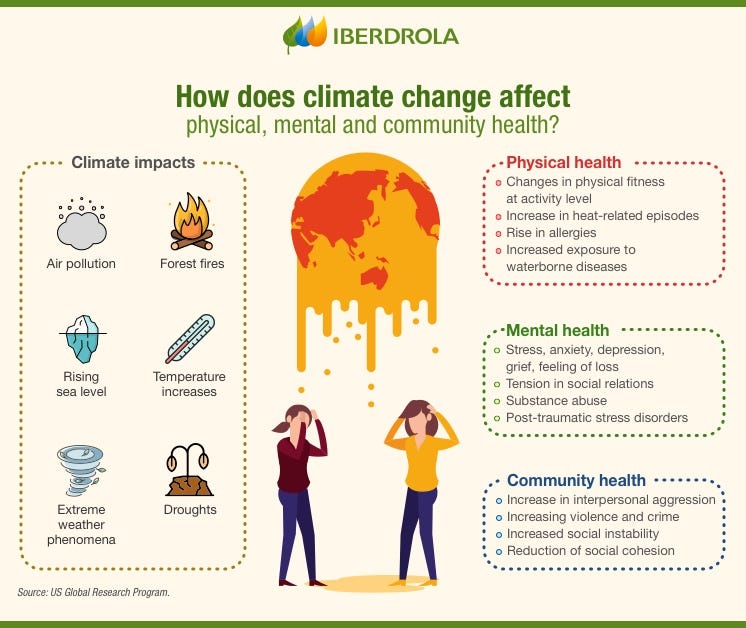

The other predicament that arises when journalists and writers forgo explanations of scientific research is that it does not empower those with the ability to combat climate change. When reading articles that focus on biodiversity loss without explaining the issue’s complexities, the environmentally-conscious will become arrogant & anxious, simultaneously proud & terrified that their worst predictions are ‘coming true.’ This is known as eco-anxiety (or climate anxiety), and it affects people worldwide. I should note that this condition is not a 21st century invention: in the 1800s, the Victorians worried black smoke from coal planet would prove detrimental to their health — maybe it would stunt their growth or cause lung disease (yep). The American Psychological Association defines the phenomenon as “a chronic fear of environmental doom;” sufferers have little belief in their ability to problem-solve, at least on their own. This is not an issue of people letting their feelings get the better of them: those who are prone to climate-anxiety often hold the least amount of power to act on their intuition. Young people and people of color, the most powerless & at-risk portions of the population, are the ones who feel the need for adaptation and mitigation most keenly. Indeed, a 2021 survey of thousands of under-25s from 10 countries found that 65% believe their government has failed their generation. This may be why Greta Thunberg’s “Fridays for the Future” protest initiative has become so popular. Mass gatherings that urge action on climate change instill hope in young people, reminding them that the burden of this crisis is not theirs alone to bear.

As covered last week, the education our schools provide often ignores the oceans, which are the most important biomes on our planet. Psychologists recommend finding inspiration in the science, but how can the youngest generations realize their potential if they can’t see the full picture? This is exemplified in an interview the BBC did with an Irish girl who attended a rally during last year’s COP26 Conference in Glasgow. She first began experiencing climate anxiety when she learned in primary school about ice melt’s effect on polar bears. Her anguish morphed into fear when she “witnessed increased flooding of Cork's River Lee and learned how extreme weather was displacing people in countries like India and the Philippines.” Again, her learning was characterized by the effects, not the facts. The trusted adults in her community did not (or were unable to) explain the complexities of severe weather & how it is influenced by sea surface temperatures. While combating feelings with logic does not always work, I believe a comprehensive education would transform people’s panic into a sense of purpose. It is likely this girl would still be inclined to join protest movements, but her motivations would be fueled by determination instead of despair.

This story also illustrates adults’ dearth of knowledge about our climate and oceans — children are often “infinitely more informed” than their parents think, according to the BBC. The psychologists they interviewed suggest accepting young people’s anxiety as logical and rational (duh). Children’s questions must be answered openly and honestly, but how can adults do this if they themselves are ignorant? It seems to me that the best cure for climate anxiety is education — not for the young sufferers, but for those whom they rely on for advice, protection, and security. Until this is rightly prioritized, parents, teachers, coaches and the like will rely on emotions instead of evidence, using memories of the calm before the (climate) storm to inform their worldview.

There was an interesting piece about this in Scientific American last year; the author, Dr. Sarah Jaquette Ray, postulated that climate anxiety is a form of resistance — to change, that is. She argues that emotions are an expression of our attachment to this world, and that the reason certain people feel so strongly about climate change is that they envision a future where they no longer sit atop the world order. Dr. Ray mentions that White folks are often at the forefront of climate demonstrations & profess the greatest distress about global warming — but as we covered above, it is poor, Black, & Indigenous communities who will likely suffer the most. The time has come when all levels of our society are simultaneously experiencing an existential crisis. Those who have dealt with generations of hardship are more resilient and thus more able to tackle the crisis if only they had the power. While sensible, her argument does not address the surface-level problem of climate anxiety, which is lack of widespread education and a dearth of fact-centered support systems. Her analysis would, I believe, be better if she mentioned ongoing literacy efforts or the unequal distribution of information not only across socioeconomic divides but also generational divides. It is true that once a problem starts affecting the privileged everyone pays attention, but interdisciplinary camaraderie can only be successful when we all share an accurate reality.

As Oscar Wilde once said, “the emotions of man are stirred more quickly than man’s intelligence.” Excessive pathos and catastrophizing helps no one: it merely deepens our divisions, either between the knowledgeable & the ignorant or along socioeconomic & racial lines. If everyone experienced a healthy amount of climate anxiety, our society would have greater environmental literacy rates; according to a recent paper, while eco-paralysis (being scared stiff) is a problem, eco-anxiety can manifest itself as “practical” and lead to the “gathering of new information and reassessment of behavior options.” Although the problem of including our oceans in the societal definition of ‘environment’ persists, it is heartening to know that people are likely to act on their emotions & bring positive change upon our world. As protest movements and correctly-directed literacy efforts grow, perhaps we will convince our leaders to flip to a new page in our climate story — one that provides the objectively best ending.

A motivational tool?

For many, it is more helpful to visualize a problem — as long as we don’t replace our curiosity with anxiety! As we learned above, eco-anxiety at its best can be a catalyst for action. And so, to aid in our understanding, we once again have an exciting and colorful map. It is a digital version of those choose-your-own-adventure stories, albeit one with only 1 good ending. To reiterate, my goal is to analogize and break down everything so that everyone can understand our oceans. A few weeks ago we looked at the University of Maine’s Climate Reanalyzer, and today for you I created a short guide to the IPCC’s interactive climate website.

The IPCC’s Interactive Climate Atlas allows laypeople to explore various data sets, choose different types of statistics to visualize, and download their own maps & models. The Atlas is designed for non-scientists & members of the public, and it shows how & where future changes to our climate will manifest themselves.

The goal is for everyone to fiddle around with climate modeling and figure out what is likely to happen in the near-, mid-, and long-term future (by 2040, 2060, and 2100, respectively). The Atlas shows changes both on land AND in the ocean, so if you were curious about acidification’s effects on your state or country’s coastline, here’s the tool you’ve been waiting for!

It will be easiest to explore the wilderness of the atlas (and not get sidetracked by the sheer volume of data on it) if we go through it together using a specific example. Let’s look at ocean acidification and see what the maps says will happen to sea water pH as the future approaches. In order to make a map, we must decide upon the parameters and the timescale by using the main controls at the top of the screen:

Main Controls

Variables: you can select different topics to look at. These variables fall into 3 categories: oceanic (i.e. sea ice concentration), atmospheric (i.e. total precipitation), and socioeconomic (i.e. population density)

Quantity & Scenario: here you can create a dataset that 1) shows the current value of your variable or 2) measures how much your variable will change. For option 1, choose “Value” from the menu and select the time period (i.e. near-term) or warming level (2C). For option 2, select the time period for a historical baseline (i.e. 1850-1900 if you want pre/early Industrial Revolution levels) as well as the future time period or warming level. You can then observe what changes will occur based on the different climate change scenarios (SSP1-5 and/or RCP 2.6-8.5). Each Representative Controlled Pathway is a different level of emissions: RCP2.6 has emissions at 0 by century’s end, RCP4.5 has emissions peak at 2040 and decline (aka following the current trend), RCP7 has peak in 2080 (aka no mitigation/business as usual), and RCP8.5 is the worst-case scenario.*

*Personally I find RCPs easier to comprehend than Shared Socioeconomic Pathways. RCPs predict the amount of CO2 emitted whereas SSPs detail how the world will adapt to the changes laid out in respective RCPs... if you’d like more information about SSPs and RCPs, check out this article or take a look at this infographic.

Season: choose the time of year to observe changes (winter, summer, annual, etc.). It will be simplest to observe annual changes.

For our example, I chose…

“Ocean surface pH”, aka measurements of the acidity, as the variable

“Near-term & SSP2-4.5”, aka business as usual, as the Value

And “Annual” as the season (to neutralize any summer/winter variability)

…to create this map of what ocean acidification will look like by 2040:

Global Map

After choosing your three controls, the map will automatically update itself using data sets. You can also choose which dataset you’d like, but I do not recommend this unless you’ve read the About section of the Interactive Atlas website. Different data was collecting used a variety of methods and in different years, so it can get confusing pretty quickly!

Regional Information

You can choose a region to look at (river basins, small islands, etc.) OR simply click on your desired part of the globe. It is also possible to account for uncertainty — but unless you are a researcher or expert, the website recommends selecting “Simple.” This is because the simple interface lets you observe a single dataset instead of combing a few.

A really cool feature of the map is the legend. If you click on different parts of it, the map will highlight those areas. For example, if we click pH 7.9-8.0, the areas of the world where this is predicted to be the new pH by 2040 are emphasized:

You can zoom in & out, change the map’s perspective, share the content or copy the URL, look at the data grid for a specific location, or compare two maps — for example, near-term acidification with far-term acidification under the same RCP/warming scenario. You can also press the “i” icon in the top righthand corner if you need some extra help, although to be honest their tutorial was more confusing than I bargained for (@IPCC hire me, you really need comms help). Let me know which scenarios you examined, if only so I don’t have to spend my days exploring the same ones! :)

Sources

Panu P. “Anxiety and the Ecological Crisis: An Analysis of Eco-Anxiety and Climate Anxiety.” Sustainability. 2020; 12(19):7836. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12197836

BBC article “How can we help kids cope with ‘eco-anxiety’?” https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20220315-how-eco-anxiety-affects-childrens-minds

Nature study https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-021-02582-8

Scientific American’s “Climate Anxiety is an Overwhelmingly White Phenomenon” https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/the-unbearable-whiteness-of-climate-anxiety/