Is Ireland really "the Japan of Europe?"

I have to admit, 'Ireocean' just doesn't have the same ring to it

When browsing my university’s catalog, I’ll admit that the course that intrigued me more than “Ulysses” or “Samuel Beckett” was the Center for Environmental History’s “Oceans and the Anthropocene.” Despite a previous disappointing experience with environmental humanities (n.b. do not pick a fight with French philosophy professors, no matter how inaccurate their ideas sound), I decided to give this class a go. Part of its appeal was the opportunity to conduct a research project on historical ocean policy of a country or town; being in Dublin, a capital city, I naturally chose to write about the Houses of the Oireachtas, or the Irish parliament. One thing that surprised me was the relevance of what I learned in my literature classes to the historical research I had to conduct for the “Oceans” essay. My professors had helped us learn about the mindset of the Irish at different periods throughout their history by reading novels, essays, and poems by significant authors. As I combed through records of parliamentary debate and public policy documents, this knowledge came alive in the words of the past.

My project focused on the past 100 years, from the onset of Irish independence in 1923 after a number of wars, to its secession from the British Empire, to its ultimately successful effort at joining the EU. This week’s newsletter will attempt to combine the most interesting parts of that paper on ocean policy with some of the cultural history I picked up in both my studies and my personal experience living in Ireland. I mentioned last week that the country has not asserted themselves on the world stage as advocates against climate change in the way that other island nations have. As you will read below, this fact is mostly due to the pungent legacy of British rule, which makes Ireland a fascinating case study for postcolonialist thought (more on that later).

Putting the “land” in “Ireland”

As I understand it, the Irish language is similar to Latin in that nouns can be changed into different declensions — for example, the noun vir, meaning “man,” becomes virī when you’re trying to say “of the man.” The Irish word for “sea” is muir, with the genitive forms mara and mar, meaning “of the sea.” After consulting both an online atlas and Google Maps, I found a couple places called Seapoint, or Rinn na Marra (one of which is a favorite swimming spot in County Dublin); a few places named Ballinamara, which means “town near the sea;” a town in County Clare called Murroogh, meaning “sea warrior”; and County Kerry is home to Murreagh or An Mhuiríoch, which means “the mariner,” and Kenmare or Ceann Mara, “head of the sea.” There is also the famed Connemara National Park in the western section of County Galway, named after an ancient tribal group Conmhaicne Mara, or “the Conmaicne of the sea.”

Also evident are the numerous anglicization of Irish words for “island” (inis becomes Inishmore and Inch, and oileán becomes Islandbridge and Islandeady, e.g.) Notably, I could not find any towns with “ocean” (aigéan or aigéin) in their name, and with less than ten places named after the sea, this suggests the native Irish did not think of themselves as seafaring people — the country, after all, is named after Ériu, the ancient Celtic goddess whose name refers to the abundant land. The spiritual home of Eriu and her family, a tribe of goddesses known as the Danu, was on the mountain Uisneach (think of it like the Irish Mount Olympus), which is only about five kilometers from the geographic center of Ireland. And since there are far more words in Irish to do with landforms like mountains, forts, valleys, rivers, and eskers, it’s safe to say that culturally, and therefore linguistically, Ireland and its people have a strong bond with the land.

Let them eat fish?

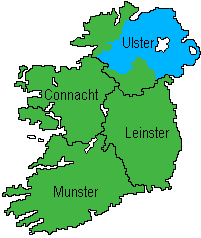

This land-people connection became part of the Irish nationalist mindset, partially because of ancient traditions but also because of Britain’s colonial policies, which sought to concentrate the ownership of the land amongst a small, elite, Protestant community. There is a long list of successful efforts to dispossess the Irish of their land: two notable events were the Ulster Plantations, started by King James I to literally sow the seeds of loyalty to the Crown, and Oliver Cromwell’s banishment of native Irish landowners “to hell or to Connacht.” Both conquests involved dispossessing people from fertile farmland and sending them into south and west, often onto estates run by Anglo-Irish landlords, where the quality of land was remarkably poorer. This obviously made it more difficult to subsist on crops and animals and had the effect of making people more dependent on the existing power structures, which were not designed to support them.

Given the proximity of many towns in Ireland’s south and west to the sea, one would assume that people would turn to fishing to support themselves. Herring, cod, and hake stocks were plentiful, and many Irish people became skilled fishermen — a visiting British fishing expert claimed that “‘no men could understand the hook fishing better than the West Coast fishermen.” The Irish Fisheries Board was established in 1818 and began granting subsidies, but just over a decade later it was dissolved in the name of laissez-fair economics (Scotland’s Fisheries Board continued to receive financial support, a fact that historian John Leaver attributes to the Scots having stronger allies in Parliament). As a result, Ireland’s fishing industry collapsed and was deemed “in desperate need of government assistance” by the mid-1840s, which unfortunately was just when the Great Famine began. Reports to the British government described how fishermen were “weakened in body from want of food” and had sold their boats and tackle to stay alive.

It was undoubtably was the policy of the British to leave Ireland’s marine resources underdeveloped — this way, a relatively new part of the country (Ireland formally became part of the UK in 1801) would not threaten the prominence of existing fisheries in Scotland. The man most responsible for enforcing Britain’s hands-off policy was Charles Trevelyan, Assistant Secretary of the Treasury. There is an ongoing debate amongst historians about whether Trevelyan’s policies were misguided or genocidal (he remains a hated figure to this day), but there is proof that Trevelyan and his staff insisted on providing no financial aid to the Irish, despite knowing about the great deal of human suffering, until it was too late. An important part of Trevelyan’s bureaucracy was the Chief Secretary for Ireland, who oversaw the practicalities of governing. The man serving in this position during the first years of the Famine was Henry Labouchere, a prominent Whig politician. It was he who informed Trevelyan of the failures of his stance on Irish fisheries, and he made a famous speech to Parliament in December 1846 after the potato crop had failed a second time, explaining to the politicians the brutal realities of the Famine’s start. Paradoxically, he also repeatedly discouraged the British government from providing relief to the Irish.

Interestingly, Labouchere’s nephew and heir, Henry DuPré Labouchere, would play another pivotal role in Irish culture by writing the 1885 Criminal Law Amendment Act, which outlawed male homosexuality and was the statute under which Oscar Wilde was convicted of “gross indecency.”

In summary, Ireland has historically relied on external powers for direction — and at times permission — regarding their ocean resources. As mentioned above, nationalists often focused their messaging and political efforts on controlling terrestrial territory, leaving a legacy of neglect in their wake. From the country’s founding in 1923, the Irish government (known as the Dáil) has consistently been baffled by the sea and have wrongly consigned themselves to a less-active role in the management of Irish waters.

100 years of servitude

The Irish Free State: 1922-1947

In these first two decades of Irish independence, only a handful of parliamentary debates mentioned the ocean, even in the context of fisheries, and when they did the government questioned its jurisdiction. After learning of illegal trawling in Irish waters, the Dáil was hesitant to add a provision about patrolling “ocean-going steamships or fisheries” to a bill because they worried doing so went beyond their authority. This is because the Treaty establishing the 1922 Irish Free State placed the responsibility for the defense of Irish waters in the hands of “Imperial Forces,” or the Royal Navy. Despite their newly granted independence, the country still relied on the British for key elements of national and maritime security. And during the one and seemingly only Dáil debate on funding oceanographic research, one representative motioned to oppose because the government has more pressing issues, namely the proliferation of “animal disease” and the “long list of waiting applicants for entrance to the veterinary college, whom the college is unable to admit because of insufficient room and insufficient funds.” In other words, they focused on onshore, not offshore, problems.

During this time period, the Dáil sanctioned the formation of the Maritime Institute of Ireland and tasked it with creating a national marine policy. However, this never happened, and the government soon turned its focus to the lack of an Irish navy during WWII. Although Ireland officially remained neutral, it depended on Britain for military protection. As a result, one minister noted that even if certain commodities could be imported to prevent shortages of food, Ireland would require their own navy to protect them, which would not be allowed under the Anglo-Irish Treaty of 1921. So, any early efforts to start managing their ocean territory were halted at the talking stage.

The Republic of Ireland: 1947-1973

The 1948 Republic of Ireland Act expunged all territorial claims by the United Kingdom to Irish waters; it also marked a significant transition in the mindset of the Irish people and their government as they were no longer part of the British Empire. The years from 1948 to 1973 were when Ireland (in theory) had the most say over its national policies. Despite this new ability to legislate within the island for the island, the Irish made little progress on marine policy. It was only after beginning the journey towards EU membership that they started establishing research centers, this despite the surge in interest in oceanography in concert with the global environmentalism movement of the 1960s and 70s.

Additionally, oceanographic research was less about proving Ireland’s scholarly abilities to the world than it was on the practical implications of marine science, implications that even the TDs themselves were ignorant about. The Dáil did occasionally discuss funding oceanographic research but only with the aim of increasing Ireland’s fisheries output. In 1972, one year before Ireland was granted EU membership, the country was described by TD Justin Keating as “the Japan of Europe” as they were the continent’s “offshore island with the tremendous fishing grounds, the huge continental shelf, the big ocean current flowing towards us and welling up on our shores with its food supplies,” giving them “extraordinary potential for fisheries and indeed for other aspects of marine science.” (Keating was the son of Seán Keating, an iconic Irish painter who is known in part for painting the men and environment of Ireland’s west coast) His demonstration of oceanographic knowledge is correct yet superficial, illustrating that they were only concerned with studying the seas so long as the Dáil maintained an economic-centric focus. Keating, who encouraged his peers to support the growth of fisheries, later clarified “when I say ‘fish’ I mean everything that comes out of the sea... I do not claim to be a fish economist.” Thus, while the Irish government may have had maritime ambitions, its representatives seemed to have little grasp of the specific goals, let alone how to achieve them.

EU Member Nation: 1973-today

It took nearly a decade for Ireland to become an official member of the European Economic Council, the organization that would become the EU in 1999, because it was not permitted to join without Britain. This is likely because, in the 1960s and 70s, the Irish economy was highly reliant on agricultural exports, mainly to the UK (Kerrygold was established in 1962 to nationalize the butter trade, for example). To combat this dependency, Ireland started granting funding to universities for oceanographic research and encouraged the development of oyster aquaculture to combat pollution in Irish waters. In this century, the government has composed two major public policy initiatives: Harnessing Our Ocean Wealth, which introduced the concept of sustainable management of marine resources in 2012, and the 2021 National Marine Planning Framework, which consists of a single plan for managing Ireland’s Exclusive Economic Zone.

Precious little has been done to publicize and galvanize the government’s interest in the ocean until recently, when climate change has climbed to the forefront of everyone’s minds. Nowadays, when marine territory is discussed, there is a concentrated effort to focus on the Atlantic Ocean, which makes up the western portion of their Atlantic territory. It is a common theme (almost a cliché) in Irish literature that the farther away from Britain one travels, the closer one comes to authentic Irishness. This legacy of finding oneself in the West persists in the minds of the Irish to this day, as evident by the focus of current research on blue-water oceanography instead of coastal pollution, instead of both: neither of Ireland’s marine planning frameworks include concrete management goals for the Irish Sea or other coastal waters that border Britain's territory.

Why should we care?

Clearly the Irish, for all their desire to move away from Britain, have adopted a mindset that does not serve them when it comes to the sea. The entity continues to be regarded, as Minister of State at the Department of the Marine Michael Joseph Noonan noted in 1990, as “a barrier to development rather than a natural resource to be utilized and developed for the benefit of the nation.” Other former colonies around the globe are in the same predicament as Ireland because they depend on global power structures to set forth outlines and directives to help adapt to the effects of climate change. This means that the organizations in charge of international policy, such as the UN and EU, are more important than ever nowadays. There is a growing trend on one side of the political spectrum to view these directives as infringing on a country’s sovereignty and identity and integrity — one example was the anti-immigration/anti-globalization riots that took place in Dublin last November — but as established above, postcolonial nations do not have the internal structure to be able to address all of their problems. Isolation, especially when discussing ocean management and climate adaptation, cannot be the answer.

Sources not linked above:

Leazer, John. “Politics as Usual: Charles Edward Trevelyan and the Irish and Scottish Fisheries Before and During the Great Famine.” Irish Economic and Social History, vol. 49 issue 1 pp 47-49, 2022.

Scanlon, Lauren A., and M. Satish Kumar. “Ireland and Irishness: The Contextuality of Postcolonial Identity.” Annals of the American Association of Geographers 109, no. 1 (December 20, 2018): 202–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/24694452.2018.1507812.

Houses of the Oireachtas. “Find a Debate.” Oireachtas.ie, April 17, 2023.

https://www.oireachtas.ie/en/debates/find/?debateType=dail.

Houses of the Oireachtas. “Ireland and the EU: Timeline of Key Events – Houses of the Oireachtas.” www.oireachtas.ie, May 16, 2022. https://www.oireachtas.ie/en/inter-parliamentary-work/european-union/brief-history/# :~:text=1974&text=Ireland%20hosted%20its%20first%20Presidency.

Interdepartmental Marine Coordination Group. “Harnessing Our Ocean Wealth: An Integrated Marine Plan for Ireland.” Inter-Departmental Marine Coordination Group, July 2012.

Even after the Gaelic resurgence that transpired in the 13th century & into the Tudor period with English control outside the Pale gaining & losing authority over the 5 provinces of Ireland (a great simplification of this medieval period of in-fighting & sectionalism among the irish kings ) it wasn't to last . One can see why the indigenous Irish - its culture & customs were only periodically strong enough to withstand dominion by the English and the Normans .