Today is the start of the UN Ocean Conference in Lisbon, Portugal. Beginning at the end of World Oceans Month, the UNOC is a follow-up to the inaugural conference held in 2017 in New York/Fiji, when delegates declared the Decade of Ocean Science. This UNOC, hosted jointly by Portugal & Kenya, is being held to support the conservation of “life below the water.” Back in 2015 the UN laid out seventeen Sustainable Development Goals to help keep global warming at or below 1.5°C; number 14 aims to “conserve and sustainably use the oceans, seas and marine resources for sustainable development.” The Lisbon conference will assess the world’s progress on SDG14 and come up with solutions for where we’re falling short.

While the UN Oceans Conference is mostly geared towards governments & scientists, there are a few things we laypeople can do to participate — more on that later.

Last week I attended a Society of Environmental Journalists webinar about the top issues facing our oceans today. The panelists included Dr. Sarah Cooley, an Ocean Conservancy scientist who worked on the IPCC Report; Justin Kenney, a counselor for the Biden administration’s Bureau of Oceans, Environmental, and Scientific Affairs (EOS); Ian Urbina, an investigative journalist; and Ambassador Peter Thompson, Ambassador from Fiji and the UN’s Special Envoy for Climate. They discussed international law, specifically on the high seas, as well as the pros & cons of environmental treaties. Ambassador Thompson and Mr. Urbina had a lively debate about the effectiveness of international agreements such as the Paris Climate Agreement. Thompson believes international accords are important because they demonstrate that countries of the world are on the same page and have a common goal. Mr. Urbina, however, stated that treaties often have the opposite effect: most of them are not enforced, which lends a certain “toothlessness” to maritime law. Policymakers think they’ve done their job, but the issues they tried to solve persist & worsen because there is no attention by journalists and therefore no accountability. Dr. Cooley made a similar point about conservation projects, noting that there is very little measurable evidence on the success of current initiatives. Scientists did not, for example, say that they would take a population census of a Marine Protected Area’s biodiversity or assess the ocean’s acidity after 10 years. When many conservation goals were established, they ironically did not take into consideration what she calls the “fourth dimension” of time: change over time. Climate change is altering Earth’s environments, yet there is no common set of measurements to determine how well the restoration & management goals been achieved. Furthermore, an environment might be politically advantageous to conserve in the moment, but would it be in humanity’s best interest to do so?

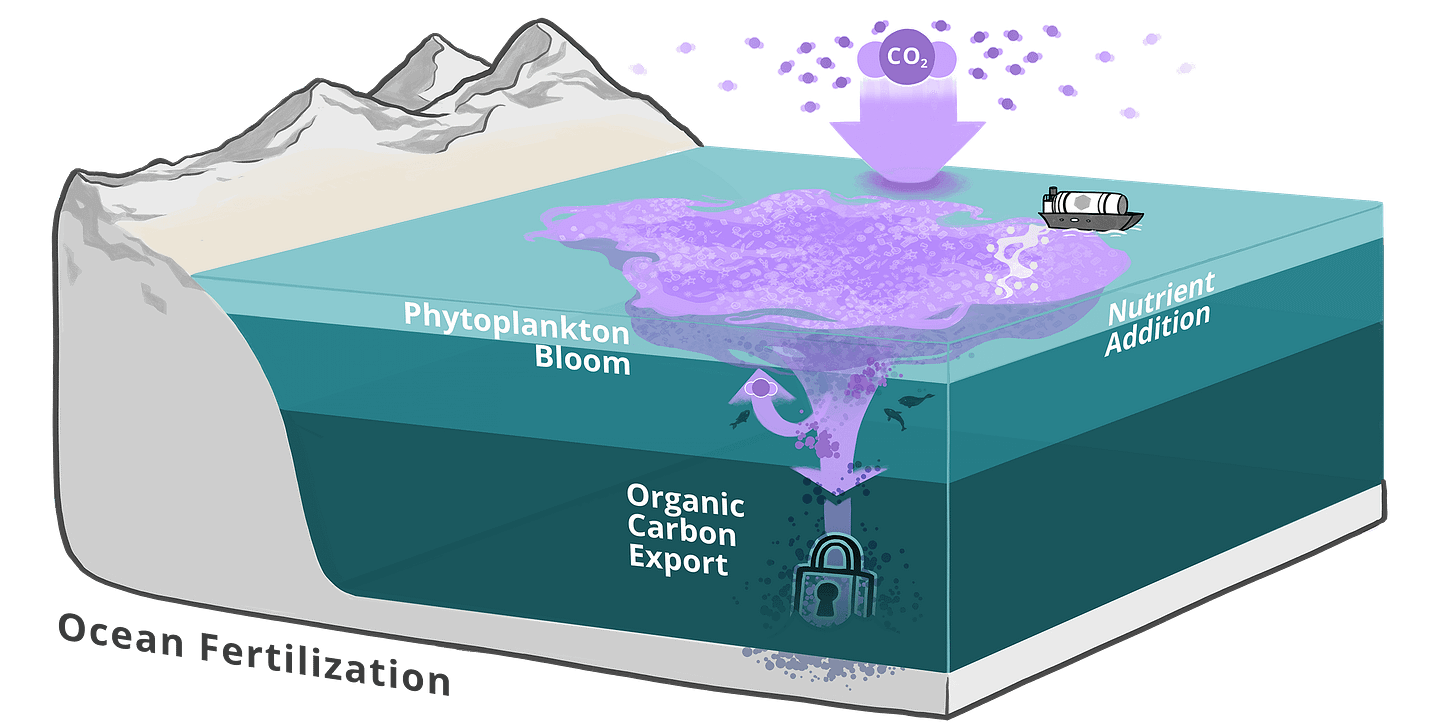

Interestingly, none of the panelists responded to my question about the potential legality of geoengineering (specifically carbon dioxide removal) in the ocean. As mentioned in previous newsletters, CDR is one way we can help decrease the impacts of global warming. Methods include marine cloud brightening, which lessens the amount of heat energy absorbed by the ocean & could be beneficial for corals, as well as ocean fertilization, which increases the productivity of plankton & helps sequester carbon in the deep ocean. One potentially outdated international treaty is the Madrid Environmental Protocol, which prevents the testing of fertilization anywhere in the Southern Ocean. Originally drafted to protect Antarctic environments, the law now seems unnecessarily strict. Is it up for discussion at this year’s UNOC? Or will it remain unamended and geoengineering, unstudied?

What is the Madrid Protocol and how does it affect geoengineering?

The Madrid Protocol, formerly called the Protocol on Environmental Protection to the Antarctic, was signed into international law over three decades ago. It designates Antarctica as a place of “peace and science” and prohibits any research activities that could possibly impact the environment and value of Antarctica. This directly bans any testing of ocean fertilization efforts in Antarctic waters. In order to conduct an experiment in the Southern Ocean, a scientist must submit an Environmental Impact Assessment to the treaty’s secretarial unit; this proposal must then go through three rounds of investigation per the Madrid Protocol. Unfortunately, the law is not permitted to be changed until 2048 without the agreement of all thirteen original signees. A strict do-nothing-for-50-years mandate must have originally seemed prudent, but this Protocol highlights Dr. Cooley’s point about a lack of anticipation of future change. The original & subsequent signees are part of a committee that meets every five years, but as far as I can tell they have made no significant changes to the original treaty. I even searched “geoengineering,” “carbon dioxide,” “removal,” and “fertilization” on their website — all terms yielded no results.

So what are carbon dioxide removal and ocean fertilization? Our oceans absorb between 25-30% of anthropogenic carbon emissions already, but it is estimated that 20% of the emissions reduction we need to keep warming below 1.5°C can come from the ocean. In order to safely increase the ocean’s carbon uptake, scientists are increasingly interested in geoengineering strategies that move carbon into the deep ocean. The most popular way to achieve this is through ocean fertilization, which involves dissolving nutrients like iron into the surface ocean. Phytoplankton (sea plants) will devour the iron, multiply into a bloom, and either die or become food for zooplankton (like pteropods!). When they or their consumers die, their carbon-rich bodies sink to the bottom of the sea and dissolve. Since 1990, thirteen large-scale ocean iron fertilization experiments have been conducted; all failed to provide conclusive evidence of net carbon export EXCEPT for one trial in the Southern Ocean. Iron here is scarce, so the potential for nutrient uptake is the strongest. However, without any relaxing of the Madrid Protocol/PEPA, any future studies of this phenomenon (was it a one-hit wonder or could it be the key to successful CDR?) or any analysis of its long-term impacts (the study was originally published in 2018 – what does the ecosystem look like five years later?) are jeopardized.

Will CDR be discussed at the upcoming conference?

Yes! Marine geoengineering will be directly addressed in today’s panel on carbon dioxide removal strategies. It is hosted by a senior policy advisor in as well as the CEO of the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute, suggesting that there is enough support for CDR in the American private sector. The panelists will address the need for establishing comprehensive code of conduct for geoengineering science as well as investigating the effectiveness and scalability of any CDR strategy. Hopefully there will be a transcript or article published about their conclusions as no details or resources were available on the UN Conference’s website. A preemptive summary of their discussions as follows:

“It is becoming clear that cutting our reliance on fossil fuels is no longer enough to address the looming climate crisis. We need to find ways to safely remove and store carbon to achieve “net negative emissions." But it is also imperative that we don’t make a bad situation worse. Several land- and ocean-based carbon dioxide removal (CDR) strategies have already been proposed that may be able to achieve the scale needed to make a dent in existing emissions. However, moving forward with any CDR strategy hinges on answering two critical questions: 1) Will we be able to durably remove CO2 from the atmosphere; and 2) Will there be ecological consequences that we can accept or that we should avoid?”

Neither the Madrid Protocol/PEPA nor any other international environment treaty are explicitly on the schedule, but the UN Convention of the Law of the Seas (UNCLOS) is. The UNCLOS establishes a duty to protect and preserve the marine environment and has been accepted by 144 nations since its initial introduction in the 1980s. Interestingly, the US has neither signed nor ratified the UNCLOS; the Reagan administration apparently believed that the US would fail so miserably at cleaning & conserving the seas that our country would be sued in the International Criminal Court! Earlier this year the US again failed to ratify the UNCLOS; some members of the Senate argued the Convention allegedly infringes on our national sovereignty. This unfortunately coincides with our reputation for not signing onto well-intentioned human rights & environmental treaties.

What is the US’s perspective on geoengineering?

While Donald Trump was in office, the US along with Saudi Arabia & Brazil blocked a UN resolution that would have established a permanent research strategy for the UN Environment Programme for both SRM and CDR. Proponents of the measure argued that geoengineering regulations deserve a permanent home within the UN framework, not just as a topic of interest for one committee (the IPCC, which released its findings on geoengineering earlier this year). Many of the countries, including Portugal, wanted to codify clear moral and ethical boundaries for the international community to abide by in order to prevent hostile nations from weaponizing science.

Indeed, research done by the Brookings Institute suggests the lack of attention to geoengineering poses severe security threats to the US (and, presumably, other Western nations). They list the UNCLOS as well as some other well-established international treaties — such as the Convention on Biological Diversity, which the US also hasn’t signed — that potentially have jurisdiction over geoengineering projects. If the US would sign onto these agreements, we could help establish a precedent for safe, ethical science experiments and would be empowered to hold our enemies accountable for misusing new technologies. Yet there continues to be no progress and halfhearted funding of any potentially earth-changing strategies. In recent years, Congress has granted NOAA a mere $13 million to investigate only solar radiation management strategies; there is no mention of ocean-based CDR on the Bureau of Oceans, Environmental, and Scientific Affairs website.

Justin Kenney of the EOS was asked directly about the US’s stance on UNCLOS during last week’s webinar. He responded that there is not currently any effort to ratify it, implying that Biden has no interest in pursuing new geoengineering avenues. In short, the Biden administration has been unsuccessful at change or expand the US’s position on geoengineering & maritime laws. At least the President was nice enough to declare June National Ocean Month, reminding all Americans of the “beauty and power” of the ocean. In doing so, he solidifies protecting marine environments as part of his agenda on climate justice & rebuilding our infrastructure, noting the importance of Indigenous communities to coastal conservation and monitoring. His declaration is a reminder that individual people can combat climate change far faster (yet with far smaller of an impact) than international leaders.

How can we laypeople participate in the conference?

The UN has a list of five action items everyday people can take to save our oceans. There is a ‘Lazy Person’s Guide’ to ocean conservation; its audience is presumably the lone individual who just this morning discovered what ‘sustainability’ means. There is no shame in taking steps to improve our consumption of resources, and I applaud the UN for encouraging people to take small steps in their everyday lives. But that is all they will be: small steps. While it’s never too late to start living sustainably, we must accept that it is the actions of the powerful few who will stop this crisis, no matter how many plants we eat and plastics we recycle (N.B. I, a vegan who relies on reusable straws, am also poking fun at myself here).

The UN urges people to start book clubs, but their recommendations are mostly geared towards children (I suppose real adults muscle their way through the IPCC Reports?). But the most ineffective action item is “organize your own beach cleanup and share it on social media using the hashtag #EUBeachCleanup,” which is ironic for two reasons. All of Earth’s beaches are at least a little polluted, but European shorelines are among the cleanest; indeed, the closest you get to Europe on not one but two recent lists of the world’s dirtiest beaches is Henderson Island, part of the British Overseas Territory in the South Pacific. Secondly, the United Nations aims to speak for all peoples, yet here they are falling into the trap of Eurocentrism. While this year’s Ocean Conference is in Portugal, they have a responsibility as global organization to encourage all countries & communities to take care of the ocean. I should mention that one of the roadblocks to reversing climate change identified by the IPCC is the lack of universal internet access. Not everyone who cleans up a beach can post about it on Twitter, but that doesn’t mean the UN should leave those people out of the conversation.

There are, thankfully, two action items that are fun and interactive. The first of which is the UN ACTNOW Campaign’s mobile app, available for Apple and Android phones. It contains far more than the Lazy Person’s Guide: there are tabs for storytelling and educational journeys, community challenges, and impact trackers. You can even earn points and ‘level up’ based on how many environmentally-conscious decisions you make each week! It is simple to download and the graphics are easy to understand. On the bottom of the home page there are news stories and a list of events, both virtual and in person, that you can get involved in. It is also possible for businesses, organizations, or private groups to start a Team where members can compete with each other to see who can take the most sustainable actions. I applied to start an In Circulation one and will let you know when they approve it!

I may be biased towards quiz games (I almost made it onto Kids Jeopardy after all), but the best thing the UN has created to help increase ocean literacy & engagement is a worldwide game of Kahoot! There are 10 questions about the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals as well as basic statistics about marine environments. For those unfamiliar with the format, you have around 5 seconds to read a question & earn points based on both correctness and quickness. I scored 6649 points, putting me in the top 50 participants. A question that stumped me was the percentage of ocean resources that are being unsustainably used, so please comment below and tell me if you knew that already. Ocean Kahoot will close on July 1st (the conference’s last day) so make sure you try and beat me at my own game before then. :)

When the UN designated the 2020s as the Decade of Ocean Science, it no doubt envisioned a future where member states solidified and modernize our global framework for protecting the oceans & climate. However, codifying maritime treaties and settling international law has become an endless cycle. International governing bodies still meet every year to craft new ideas that involve changing some already-existing laws and treaties. Then another conference must be planned to discuss these amendments — assuming everyone has agreed to them, of course. It has become so complex to cover that the only mainstream article written about this year’s UNOC was Reuters’ coverage of Jason Momoa’s beachside speech. Alas, it seems the international community is as scattered as a classroom during the final weeks of school. And while our leaders finish planning for our last few lessons, we’ll gladly be distracted by a game of Kahoot!

Sources not linked above

"Uncle M" got 6630. Who could this mysterious stranger, who apparently is more knowledgeable than even the brilliant Prof. Budd, be?!

I got 5693