Political Theory Under the Sea

A few things Sebastian the Crab *didn't* sing about

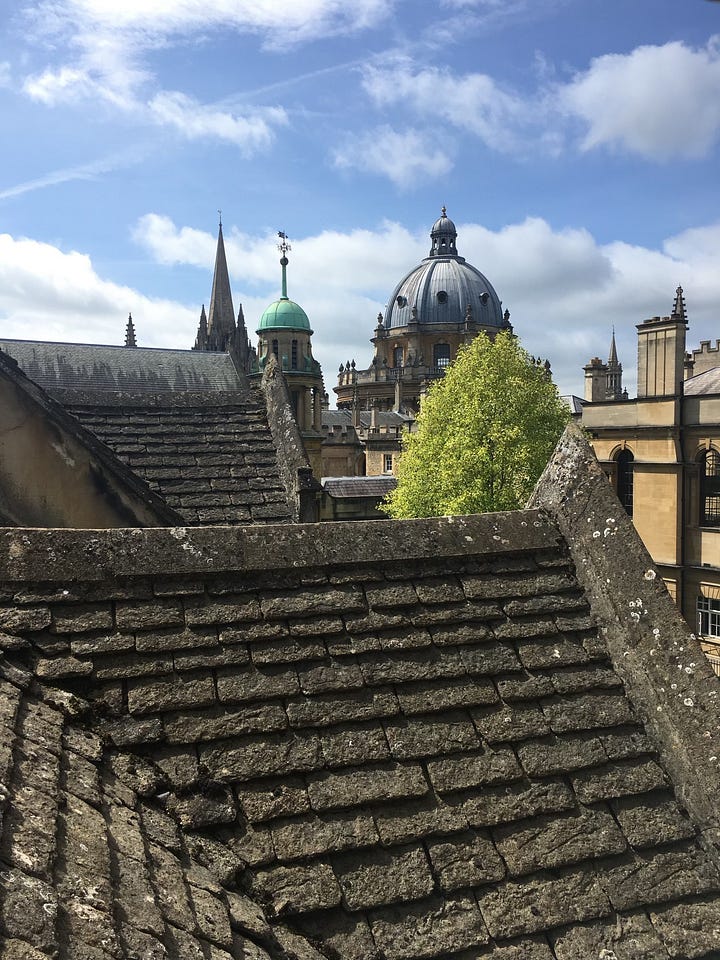

Six years ago this month, I flew to the UK to begin my year abroad at Oxford University. The first month of that year was spent among other Americans and involved learning how to survive in this new, rigorously academic environment. We were enrolled in a Humanities Seminar, where tutors led discussions of everything from Herodotus’s Histories to Henry James’ The Turn of the Screw (still a favorite of mine). Those few hours each week laid the foundation for some wonderful friendships, and they also taught us all how to articulate our beliefs and opinions through the lens of whichever work we had read.

Towards the end of the seminar, the tutors organized a walk through Port Meadow, a beautifully wild area of common land. The path was rather narrow, so we ended up walking in groups of two or three. My ‘buddy’ was a girl from Princeton; we talked of her extensive travels around the globe and what subjects we studied. I found myself eagerly explaining everything I had learned during my previous semester’s course on Global Climate Change. As always when one discusses global warming, the conversation flowed into politics, and I half-jokingly said that our planet is doomed unless every government takes immediate action. She responded something to the effect of “My friends and I are so worried about climate change. We always talk about how big of a crisis it is, and sometimes we’re like ‘should we even have children?’ Because it’s really not ethical to bring a child into a world that’s collapsing!”

This opinion so surprised me that I had to make a conscious effort to keep walking. Perhaps she was trying to seem intellectual, but to me her attempt at constructing an ethical dilemma seemed laughable. At first thought, her point seems logical — if there were fewer people on this earth, of course fewer resources would be used. But like nearly all climate solutions, the choice not to procreate would only make the planet more livable if a majority of people participate in the endeavor. Humanity will continue to ‘be fruitful and multiply’ regardless of the decisions of privileged individuals who can easily and consistently access reproductive healthcare.

Some readers may be surprised to learn that this student’s opinion is far from fringe. A July 2024 Pew Research survey found that 26% of childless adults under age 50 have refrained from starting a family because of “concerns about the environment.” In response, a pregnant environmental journalist at the LA Times cleverly noted that this line of thinking misplaces the “pressure” of solving climate change on women instead of “oil companies, large corporations and international governments driving the majority of climate change.” Unfortunately, her article is an outlier compared to other recent discussions of the ethics of pregnancy amidst the climate crisis. Articles in the Harvard Gazette, Yes Magazine, and the New Yorker often center philosophers and academics who engage in a delicate dance between hope and nihilism.

However, this line of thinking seems merely to highlight its proponents’ savior complexes while raising several questions for those who debate in good faith: Does choosing not to procreate give one moral superiority over people with the same resources who make a different choice? What about the tens of millions of people in resource-poor countries, who do not have the luxury of participating in this thought experiment? Or indigenous groups, who have historically struggled with maintaining healthy population numbers? In short, how broadly can this new ethical standard be applied?

The New York Times’ ethics columnist reminds us when we “universalize the maxim” it often brings about negative social change. Indeed, the belief that humans are environmental hazards is one of the tenets of eco-fascism. Eco-fascists think the only way to solve our environment’s problems is to diminish the amount of people on this planet. While a benign example of this philosophy in action is a couple’s choice not to have children, more radical individuals typically used it as an excuse to commit mass murder (e.g. the 2019 shooting in Christchurch New Zealand and the 2022 Tops supermarket shooting in Buffalo NY were both committed by men with eco-fascist manifestos). On the flip side, some of Greta Thunberg’s critics accuse her of spearheading a campaign to center eco-communist and eco-Marxist propaganda in the climate narrative. These (White ultra-conservative) men usually point out that she focuses most of her energy on criticizing capitalism instead of promoting nature conservation. Perhaps if they were stronger debaters, they would write about resource use versus resource exploitation instead of dismissing Thunberg as another mouthpiece for “anti-Western communist ideology.”

Thus environmental theories that once seemed radical or esoteric are entering the climate activist chat. Given the recent resurgence of philosophy in pop culture (anyone else enjoying the Charli Marx-cx memes?), I was curious as to what these schools of thought say about the state of our ocean. My findings are the subject of this week’s In Circulation.

Notes on marine resources

One of the largest environmental issues, both historically and today, is that of resource depletion. Usually when policymakers refer to ‘marine resources’ they’re talking about commercial fisheries, but the ocean has an aesthetic as well as monetary value: in 2022 the largest component of the “marine economy” was tourism and recreation, according to the US Environmental Protection Agency. But sea level rise, changes in global circulation, and increasing water temperatures are all climate change-induced problems that make coastal waters uninhabitable for fishes and less enjoyable for humans. As mentioned in previous In Circulations, the ocean absorbs tons more carbon than any terrestrial environment (the seas do, after all, cover 71% of Earth’s surface). But all this excess carbon is causing the ocean, which is slightly alkaline/basic, to slowly lose its power as a carbon sink through a process called acidification.

That climate change is amplifying existing environmental problems like overfishing could be why 21st-century scholars argue in favor of “taking the depletion of marine environmental resources into account during planning, governing and decision-making.” (Wang & Chen 2006) Traditionally, governments and NGOs went about solving the problem of resource depletion by working to preserve the land — in the United States, the fin-de-siecle sustainability movement was spearheaded by John Muir’s Sierra Club and President Teddy Roosevelt, who created over 150 national parks, forests, and nature reserves. The environmental movement in the early 1970s expanded on these priorities by advocating for the passage of the Clean Air and Water Acts, which codified the government’s responsibility to not just protect but improve the quality of land-based natural resources.

While increasing the number of national parks, lowering air pollution, and purifying drinking water enjoyed broad support, a quieter movement to conserve maritime resources was developing alongside. According to the National Marine Sanctuary Foundation, the earliest ocean conservation efforts took the form of “seaward extensions of terrestrial protected areas” aka conserving the waters around coastal and island wildlife refuges. While certain states had enacted localized marine preservation laws, it wasn’t until 1972 that Richard Nixon begrudgingly signed the Marine Protection, Research, and Sanctuaries Act (MPRSA) into law. Interestingly there are no photos of him signing this bill, and his only comment on its passage was about water pollution, demonstrating his lack of interest and/or understanding of the bill’s potential. For contained within the MPRSA was a provision called Title III, which enabled the founding of a national body to create and maintain marine sanctuaries.

After the Rio de Janeiro Earth Summit of 1992, nations made a pact to conserve 10% of global ocean territory by 2010, but as of 2023 only 7% of the ocean is part of a marine protected area (MPA). The slow pace of expansion is due in part to the lack of conservation law enforcement on the high seas: last year The Economist wrote that managing MPAs “is an incredible challenge,” but this fact should not discourage leaders from rallying “political will and increased investment” to protect 30% of the ocean by 2030…! As British policy researchers John Humphreys & Robert W.E. Clark note in their recent book, such proposals are effectively doomed unless leaders take “a comprehensive global conservation strategy [that applies] to 100% of the marine environment.” In other words, the actions inspired by the current mindset are insufficient, so instead of doubling down on our behavior, we should consider adopting a different philosophy.

50 Shades of Green?

There is a decent amount of scholarship on ecological applications of different political philosophies like fascism and socialism. As I’ve written before, the ocean is often omitted from our conception of the environment, so I was disappointed but not surprised to read that contemporary philosophy and sociology has an “ocean deficit.” Sidney Dobrin notes in his 2021 book Blue Ecocriticism and the Oceanic Imperative most environmental theories have “thus far primarily been … land-based criticism[s] stranded on a liquid planet.” Instead of listing a series of ‘blue’ movements, I will instead outline of each school of thought and explain how it is, or could be, applied to the ocean.

Eco-Fascism refocuses the blame for climate change on certain groups of people as opposed to all of humanity. It suggests that “certain people are naturally and exclusively entitled to control and enjoy environmental resources,” rendering some human populations “native species” and others “invasive,” according to University of Connecticut professor Alexander Menrisky. Given the lack of humans living under the sea, it makes sense that there is no mention of the ocean in most eco-fascist manifestos and political platforms. But an eco-fascist marine conservationist might fixate on the limited supply of fish stocks and argue that these resources should only be used to feed certain (superior) people.

Eco-Socialism, by contrast, promotes the idea of common ownership of Earth’s resources. These people believe the scarcity problem can be solved by building a future where people live in harmony with both the natural world and each other. Eco-socialists blame capitalistic exploitation for climate change, something they share with the eco-Marxists of the world. Groups like the Climate Justice Alliance and the Sunrise Movement are eco-socialist because they believe any and all climate adaptation projects must be distributed equitably across society. Unfortunately, these movements barely acknowledge the ocean except for the Sunrise Movement’s anti-plastic pollution advocacy program. But an eco-socialist marine conservationist may argue for protecting ‘nature for nature’s sake,’ working to prevent habitat destruction and emphasizing the interconnectedness of the land and sea.

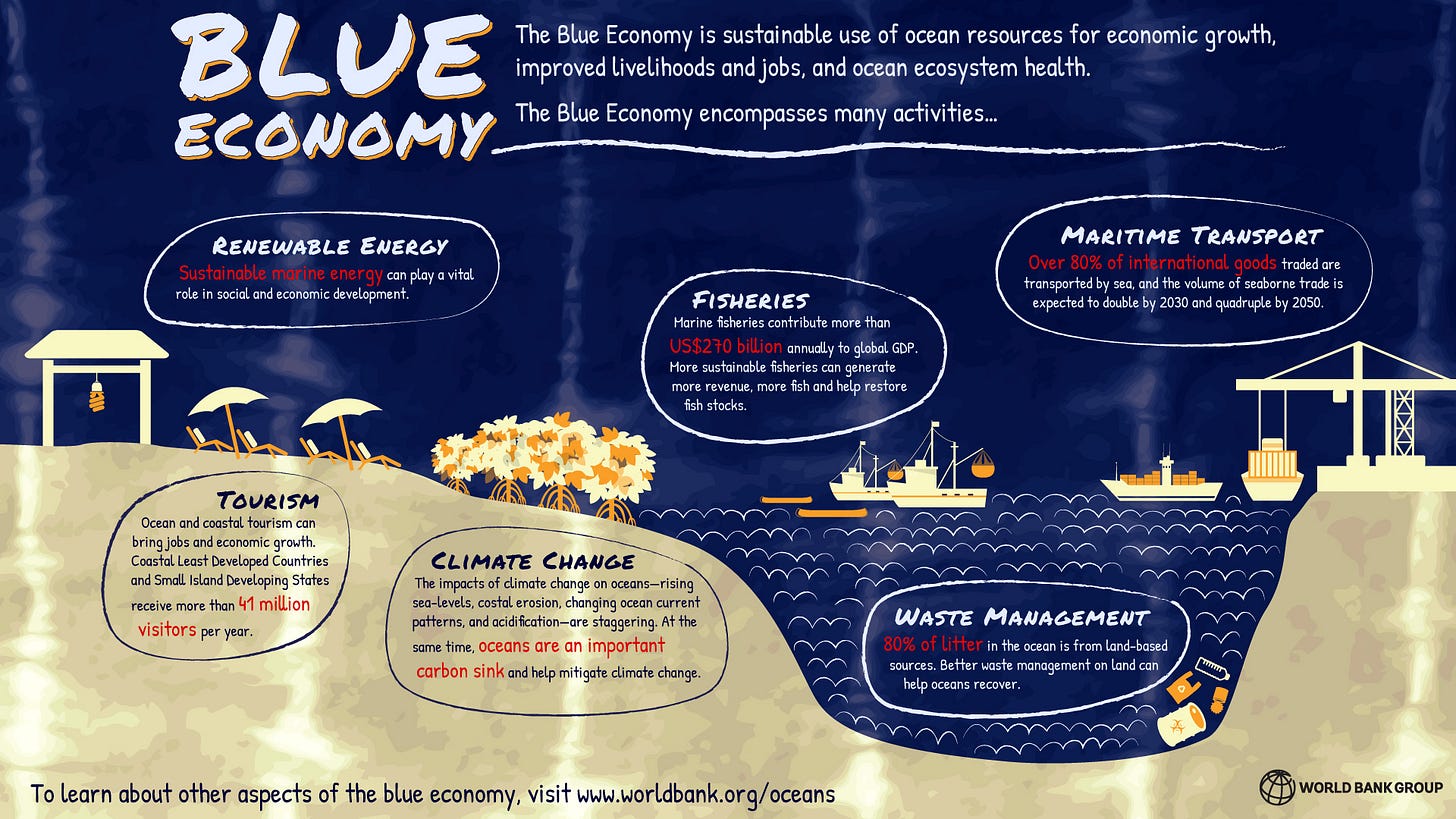

In the face of all this criticism, capitalism has recently undergone a rebrand: companies are investing in environmental projects like carbon credits and working to ensure every step of production is sustainable. As the blog Human Rights Pulse observes, this has resulted in the commodification of sustainability and pervasive greenwashing, or portraying a product as eco-friendly when it really isn’t. A cynic would say the shift towards eco-capitalism is only motivated by the desire to extend the lifespan of non-renewable resources, but a supporter might argue in favor of this well-intentioned shift towards making the means of production align with the values of consumers. I was surprised to find a thriving blue capitalism movement, spurred on in large part by recent discussions of the so-called ‘blue economy,’ which according to the UN aims to involve small island and coastal nations in the global economy by sustainably engaging with both human and marine resources. Applied on a smaller scale, this concept makes room for companies like 4Ocean to capitalize on the ocean’s problems by making jewelry from ocean-polluting plastics. Ultimately, eco-capitalists advocate for the sustainable use, or protection for future use, of marine resources and habitats. They may argue in favor of conserving ocean environments but only so that aquaculture businesses, island tourism industries, and deep-sea mining can thrive.

Evidently, these schools of thought are far from interdisciplinary. For all eco-socialism’s emphasis on inclusivity, eco-fascism’s monomania for resources, and eco-capitalism’s desire to problem-solve, their efforts to ‘go blue’ are sea-green at best. Thus the problem isn’t that our marine conservation philosophy is failing us — it’s that no one has made space for it in the current conversation in the first place.

“The human world, it’s a mess!”

Next year will mark the halfway point in the UN Ocean Decade. According to UNESCO, the Decade now has over 600 initiatives endorsed by more than 70 countries. These actions range from expanding ocean literacy to including indigenous knowledge in conservation plans, but importantly they emphasize the importance of relying on science-based solutions — their slogan, after all, is “The Science We Need For The Ocean We Want.” And despite the inconclusiveness of philosophies outlined above, there is evidence that simply setting aside parts of the sea has proven successful. In a 2020 paper published in Nature by Duarte et.al., scientists and economists analyzed the strong recovery rates of habitats and animal populations that were part of well-enforced Marine Protected Areas. They concluded that expanding the scale of such MPAs could help restore the “abundance, structure and function of marine life” by 2050.

So does this hands-off approach align with the ideas of eco-socialism, or is it merely laissez-faire blue capitalism? Does the fact that MPAs must be heavily policed mean that eco-fascists have a point? No matter one’s philosophy, our ultimate goal is to create a more livable world. While conservation policies have traditionally been very people-centric, initiatives like the UN Ocean Decade have helped humanity see the sea as part of our world. In fact, a few lessons could be learned from Disney’s The Little Mermaid, in which Ariel sings about transcending the boundaries of land and water. Indeed, her musing at the beginning of the song “Part of Your World” — ‘I just don’t see how a world that makes such wonderful things could be bad’ — reminds us we have the potential to do better. So perhaps the solution is to spend less time thinking about what’s right, and more time doing it.

Sources not linked above

Duarte, C.M., Agusti, S., Barbier, E. et al. (2020) “Rebuilding marine life.” Nature, vol. 580, pp. 39–51. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2146-7

Humphreys, John and Robert W.E. Clark. (2020) “A critical history of marine protected areas.” Abstract. Marine Protected Areas, Elsevier, pp. 1-12, ISBN 9780081026984, https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-102698-4.00001-0.

Li, Z. (2021) “Some Thoughts on Ecological Marxism.” Open Journal of Social Sciences, vol. 9, pp. 212-219. doi: 10.4236/jss.2021.912014.

Wang, X. & Chen, W.. (2006). “The depletion of marine environmental resources caused by human activities and its monetary evaluation.” 5th International Conference on Environmental Informatics, ISEIS 2006.

EPA.gov climate change and marine resources | Rubicon.com history of sustainability | NMSF history of marine sanctuaries | University of Warwick eco-marxism | Sierra Club eco-fascism | The Guardian green capitalism | Guts Magazine blue capitalism | World Bank white paper on the blue economy

Well written piece! Thanks for the clear, concise and unbiased explanations of eco socialism, fascism and capitalism. I have a deeper appreciation for the ocean being the big blue elephant in too many rooms. As a child of the 90s, I also appreciate the Disney references :)

Makes some great points that there are those on the eco- fascist& eco -capitalism side that see only one perception : either to prove that sustainability of resources is enough -without doing what is necessary to enhance the limited ocean resources in nature-or in the case of eco- capitalism to protect certain industries ( fisheries for ex.) from exploitation without addressing the economies of certain nations to understand what can be achieved through sharing vital resources by negotiations of equitable treaties.